Hive Center for Contemporary Art is excited announce the opening of Zhang Ji’s latest solo exhibition, “Phowa”, at Hive Shanghai on 6 November 2024. Following “Kundalini” (Hive Beijing, 2020), “Bardo” (West Bund Art Fair, 2021), “Manas” (Long Museum, 2023), “Sign” (Suhe Haus, 2023), this will be the artist’s fifth presentation. The exhibition is curated by Yang Zi and will be on view until 11 December.

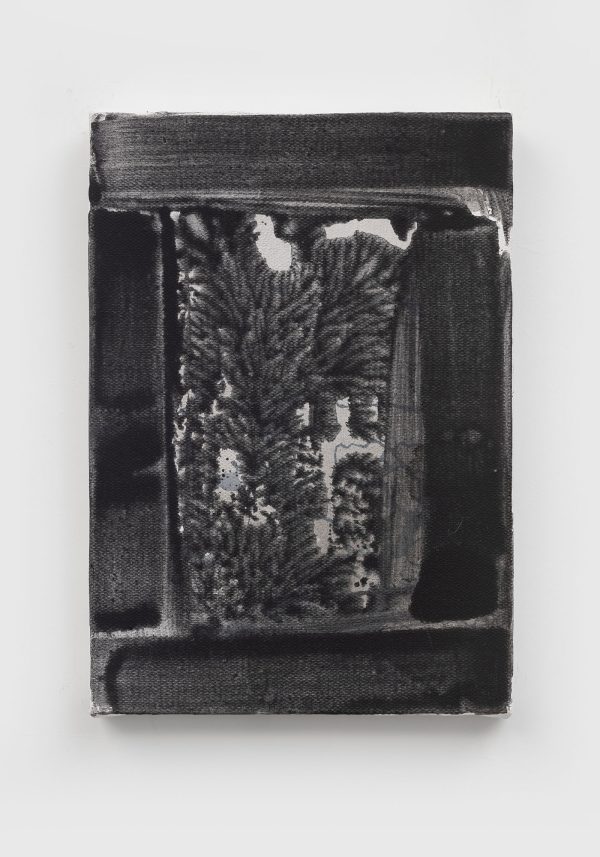

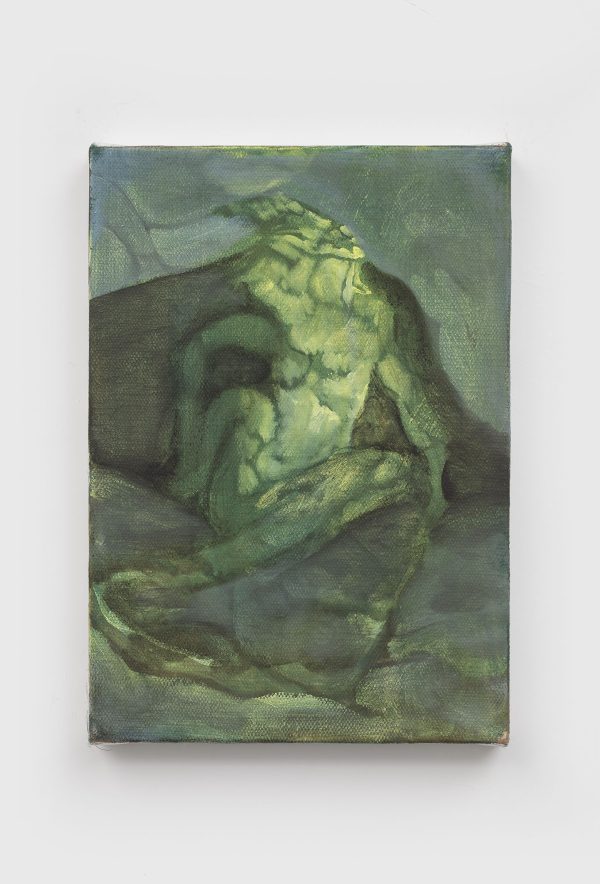

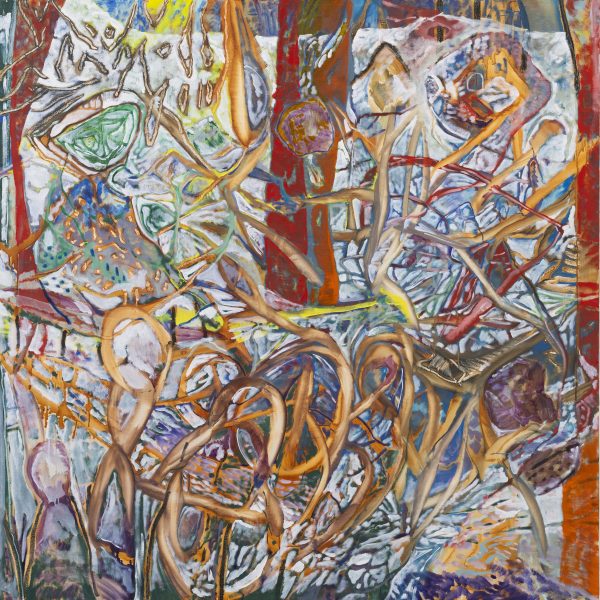

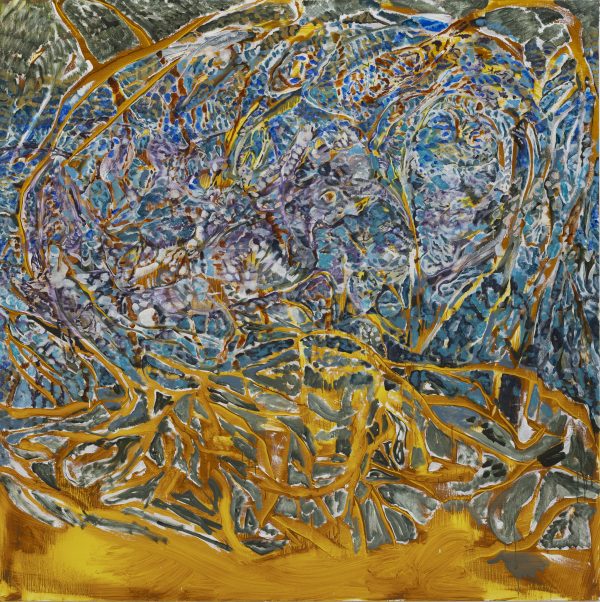

The exhibition “Phowa” (the title of the exhibition implies an intention of escape, as he seems to draw the boundaries of his own unperturbed territory) features a series of paintings that are inextricable from each other. One distinct overall characteristic is his attempt to sever his relationship with the established heritage of painting without parading it, and even preserving the traces of his infiltration in it with genuineness. This has often caused him to be mistakenly labelled as an “abstract expressionist” painter who works with emotion and inspiration – even though he immerses himself in a state of total concentration and devotion during the actual practice. We can recognise his working habit of making continuous decisions in his practice. His careful selection of pigments, colours, and other mediums (wax, charcoal powder, and resin) reveals a scientific mentality. Applying different pigments to paper swatches, Zhang Ji repeatedly ponders and compares the sensory impacts they can trigger. Compared to the extensive process of pigment research, the pace at which he makes decisions while painting is more intensive and invisible.

The preparation work leaves the artist with enough space and distance to complete one image and then immediately move on to another that is not entirely influenced by the stylistic ideas of the former, creating an organic connection, dialogue, and intertwinement between the two while still remaining as coherent as possible: these paintings are done with the wet-on-wet technique, that is, they are outlined and painted without making a rough draft, and executed in the most intensive period of time possible. The large-scale works on canvas absorb the images of the smaller works on paper, those may be read but not instantly. In this way, his paintings are neither subjected to the laws of “purity and self-criticism” nor chained to the paths of interpretation (which, for painterliness, is a kind of superficiality) that the cultural milieu attributes to a specific image. He perceives the movements of painting as a dance, which can be split into different still fragments, but without any suspension of the rhythm. A rigid dance is as bad as a dogmatic painting.

The texts written by Zhang Ji establish a parallel relationship with the paintings and attempt to disclose the details of the images in the paintings. Different images are threaded together like poems, forming verses such as “The child of silicon needs milk to grow up, so cancer is born” and “The girl turning back becomes two in one”. Sexuality, occult phenomena, and thoughts about painting – these often surfaced in his mind are captured. Individual consciousness is used by him as a tool to anchor his creative objectives. Pleasantly and harshly, he works with it with the intention of finding what is alive, free, and vital. For him, that is what painting should be.

-600x283.jpg)

Grown-from-Statue-2024-布面油画-Oil-on-canvas-225×185cm-1-600x725.jpg)

a-Still-life-Painting-of-Shell-Face-2024-布面油画丙烯-Oil-acrylic-on-canvas-220×240cm-600x509.jpg)

Fading-Shell-with-Holes-2024-布面油画丙烯-Oil-acrylic-on-canvas-275×275cm-600x606.jpg)

Fading-Shell-with-One-Hole-2024-布面油画-Oil-on-canvas-253×253cm-600x599.jpg)

Statue-Potted-2024-布面油画-Oil-on-canvas-195×195cm-600x600.jpg)