Voyager 1, NASA’s space probe that launched in the 1970s in exploration of the Solar System, made its first foray into a different world as a spacecraft carrying fragments of human civilisation. In photographs captured by Voyager 1 from 6.4 billion kilometres away, humans managed to observe the Earth from a distance so far away that it became a tiny speck of light with only 0.12 pixels. This seems to justify the uniqueness and fragility of the world we inhabit and navigates a subtle displacement between the microscopic and the macroscopic. If, at the time, Voyager 1 carried with it the desire to depart from the narrative of a particular subject, the project “Voyager I” envisages an autonomous community of individuals or small, everyday units adrift outside the solid confines of the common imagination, in the hope of reaching out to the possibility of deciphering the broader established social framework and attempting to extrapolate a more complex complicity.

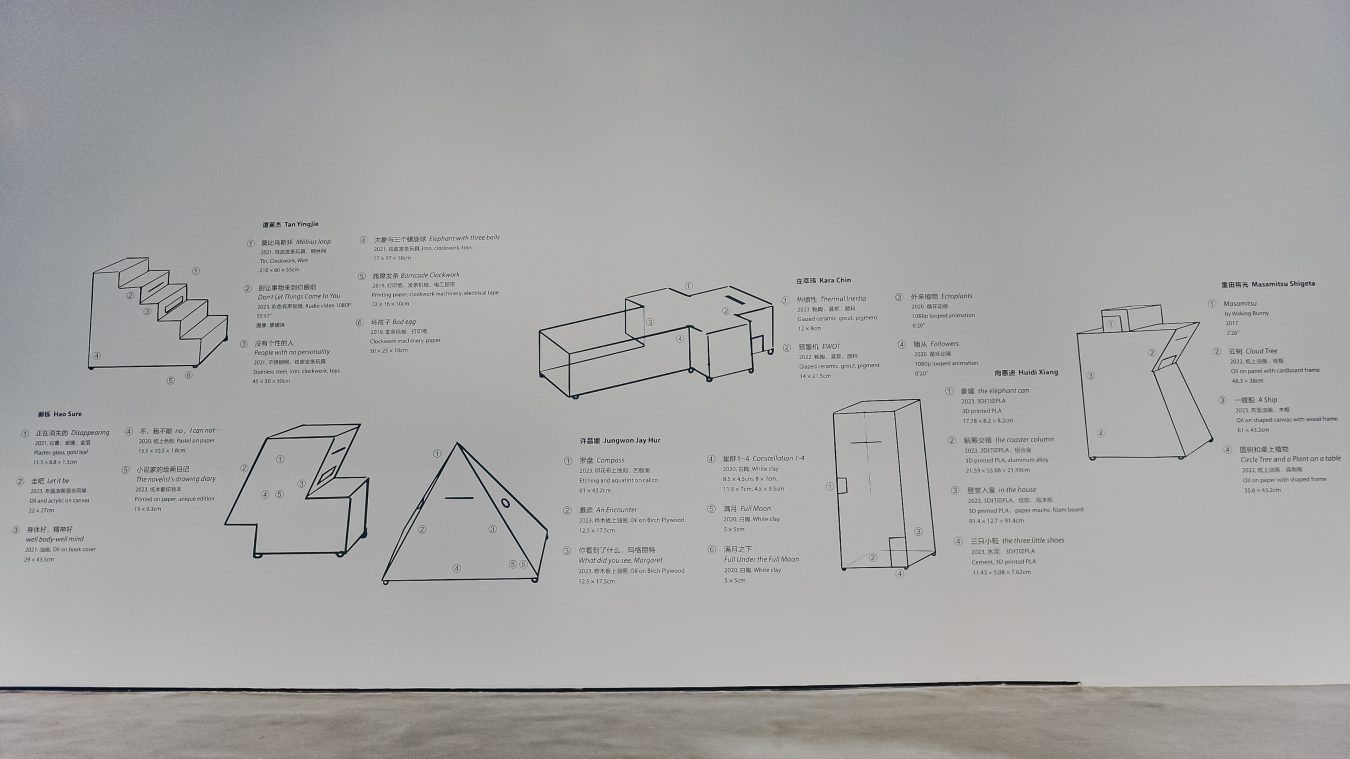

“Voyager I” is on view from 22 December 2023 to 27 January 2024 at Hive Becoming in Shanghai. Using Hive Becoming as project space for the first time, the project envisions a more dynamic approach to production in the same way that the Voyager 1 spacecraft explored the Solar System by releasing the inertia of the system from its closed loop. This project takes six performance installations from artist Tan Yingjie’s directorial theatre, Don’t Let Things Come to You, performed at Long March Independent Space, as the exhibition spaces, where curator Tang Yifei invites six artists, Kara Chin, Hao Sure, Jungwon Jay Hur, Masamitsu Shigeta, Tan Yingjie and Huidi Xiang to participate and become the hosts of the six boxes, sharing some of their personal encounters with the world in their respective 2-3 square metres of space, showing artworks that include paintings, sculptures, installations, videos, writings, and sound pieces.

Below are character biographies of the artists residing in the six boxes.

1

Kara Chin is fascinated by traps, whether visual, technological, or institutional. Her computer is filled with various models and robotic parts of different scales, and she regularly watches videos of robots at work and different kinds of mechanical products, as well as Sci-Fi or films about ghosts. In fact, these are all about the conflict of ‘juxtapositions’, the distance between the reality of viewing and the reality of seeing, the distance between the organic and the synthetic, i.e., how technology can exacerbate the disturbances or propel the future. Chin’s box plays with the logic and vision of a film set, inside which a miniature cinema is constructed, with a tumbling flood of popcorn behind a miniature screen, seeming like doomsday. The virtual sculpture that runs at an even pace in the animation – a device that purifies the electromagnetic field – appears as the religious relics of technology, enacting on false peace and faith.

2

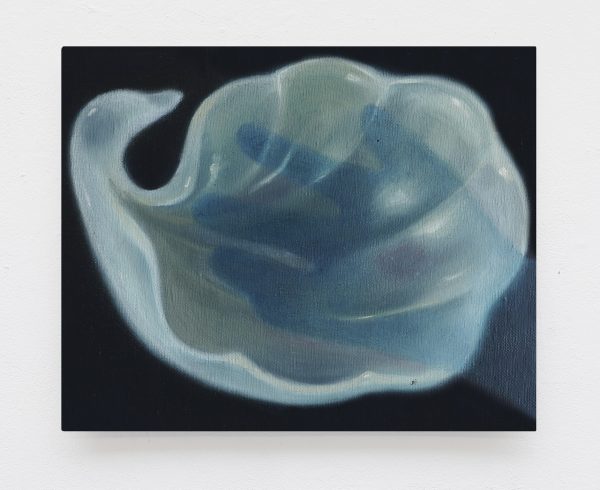

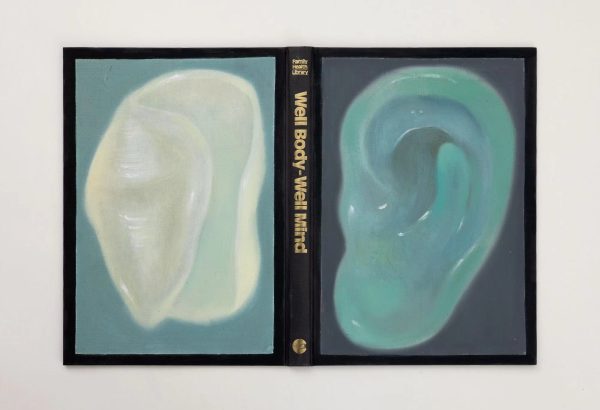

Hao Sure often feels as though she is in spiritual practice; the kittens that keep appearing on the way from her home to her studio, the flock of pigeons that stand on the balcony of her studio and watch as she paints – these are the moments that can be described as miraculous in this spiritual journey. More often than not, she would come close to the state of a chanting monk, painting in her studio for a long time without any other decorations or soft chaises, her body, being on the ninth floor, the top floor, gradually ascending with her consciousness during the creative process as if she was flying. This entailed form of sweetness and pain is also embedded in her observation and reading of the world, where writing and painting, Renaissance sculpture and jade statues, religion and mythology are constantly dissolving and metamorphosing in her practice with the bodies of different creatures bearing their emblems. Just like the hidden ear outside Hao’s box, she filters and rearranges the narrative of the external world into her own – inside the box is her writing desk in the corner.

3

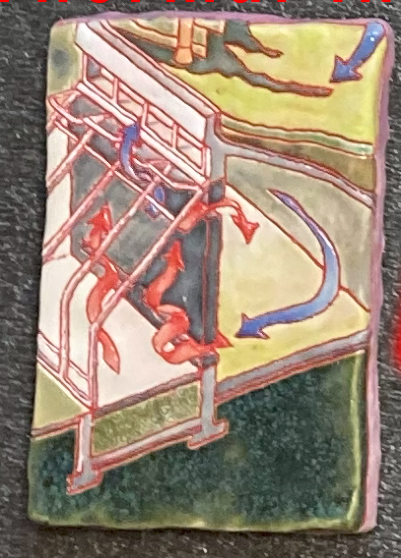

Jungwon Jay Hur has many rituals to live with herself. From the moment she wakes up in the morning, a burning stick of incense in a small shrine accompanies a personal pronouncement for the new day – about the work, the world, and indeed anything. Before starting to work in the studio, she reads a chapter of a book or picks out an album to listen to; before leaving the studio in the evening, she sits in an armchair in judgment or confession as if she were the judge of her own work. These tangible and intangible ‘languages’ are an interest to Hur, establishing their certainty from indeterminate forms through painting, printmaking, ceramics, and woodwork, drawing on visual references such as art historical paintings, Korean and Western folk music, and 20th-century European films to create a reinterpretation of intangible cultural heritage that intertwines autobiography and fiction. Her box becomes a station or a monument, where covered printed fabrics, landscape and portrait paintings on birchwood along the grain, and ceramics of allegorical elements reactivate the gears of cultural history.

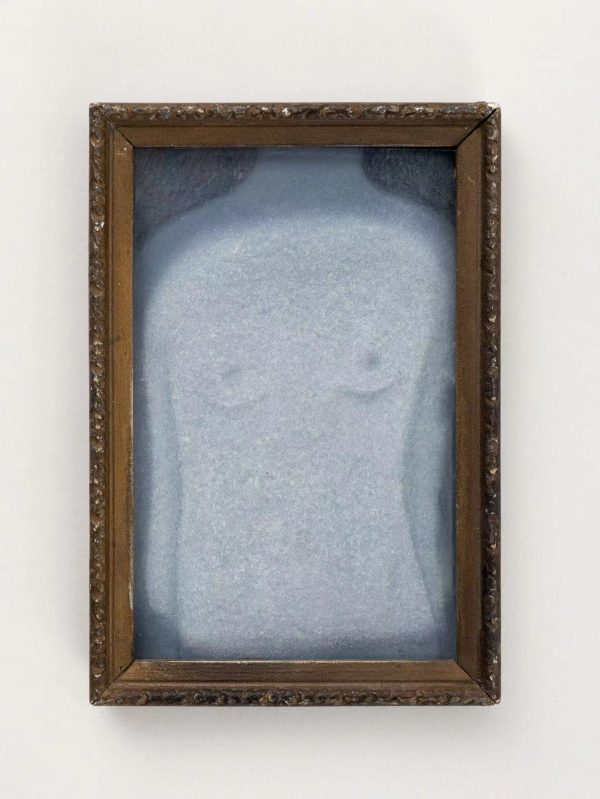

4

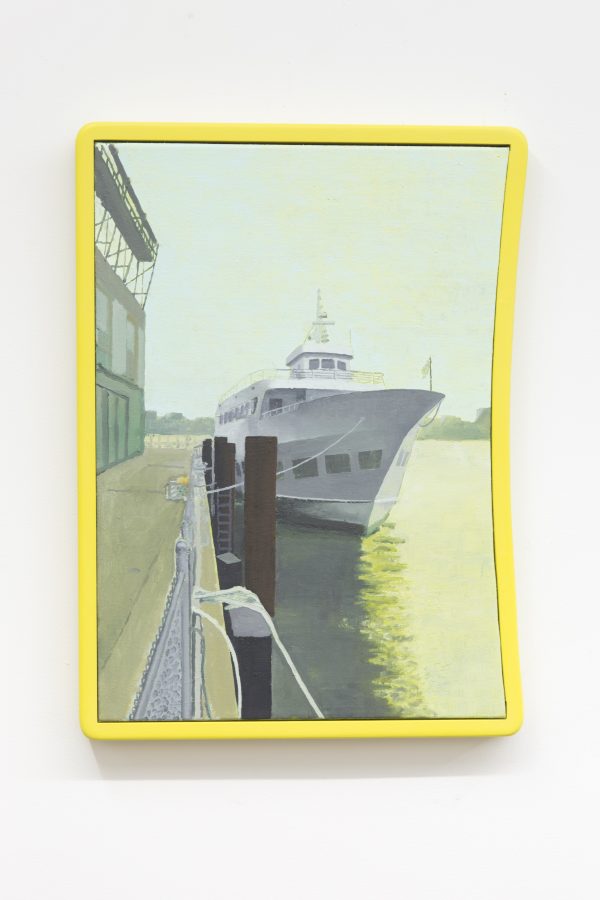

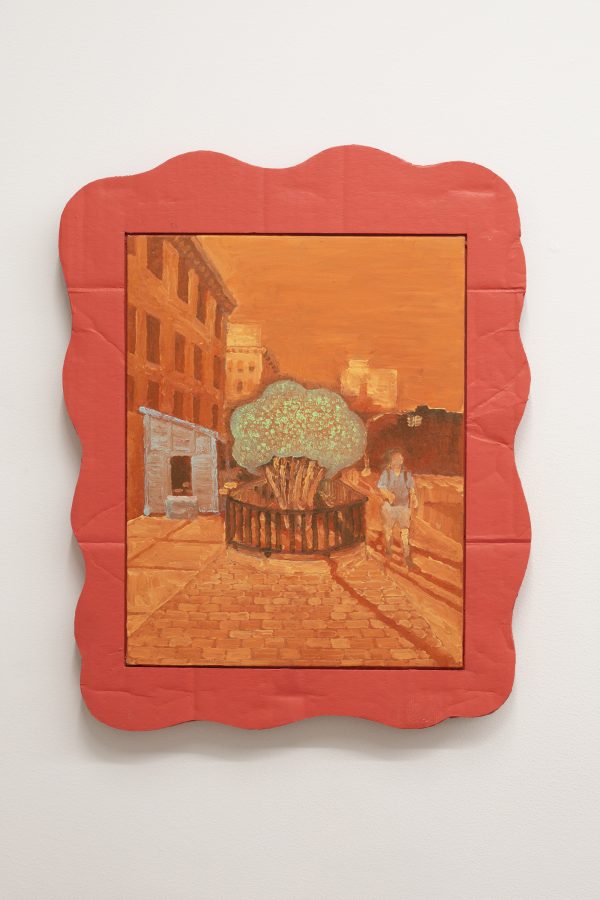

Masamitsu Shigeta cross-understands and practices his painting and music, arriving at his studio to play classical guitar to awaken his fingers before starting to paint. Like a field recorder collecting the sounds of the outside world, Shigeta captures the different frequencies that appear in the cityscape, their different shapes, scales, and tones projecting the city’s speed, rhythm, and tempo. Once tired of painting, Shigeta began to create frames for his work, moulding the shape of the canvas or framed installations, which are often made up of materials found around the city or discarded in his studio. This also became a recording of the visual environment he created in relation to sound and place. The combination of different curves on the surface of the box echoes the alignment of sound bands and frequencies, and the small box on the top houses Masamitsu, an absurd ‘symphony’ from the eponymous track by his former band, Walking Bunny.

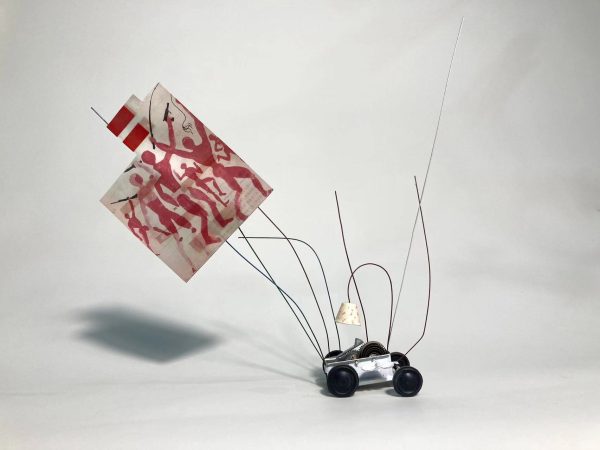

5

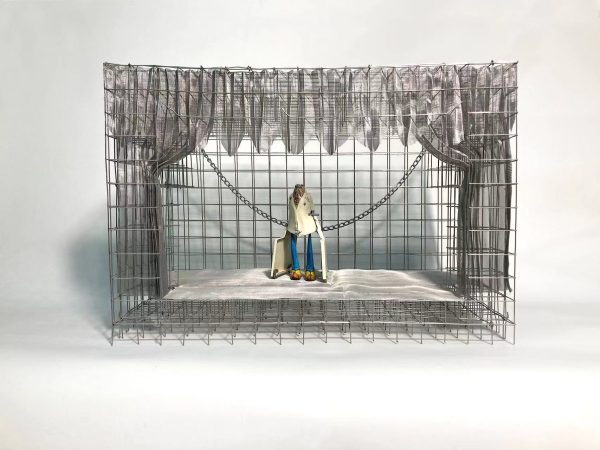

Tan Yingjie plays an old game called ‘Three Kingdoms’ every day, replacing his alarm with being urged on quests by his group chat friends at seven in the morning. He would, then, go to work in the studios with high-ceiling single-storey houses and storage, enter the joyful ruins – converted abandoned film props and furniture, metal sheets and wires, other assorted materials, cabinets full of wind-up toys, countless graphic fragments, etc. Among these scattered objects are models of works in progress, as well as already-assembled installations and sculptures. Like the state of his studio, Tan Yingjie’s practice emerges as a result of objects invading each other bearing their own space, critically visualising perceptions of contemporary experiences. The big and the small theatres in his box- a contemplation of the individual’s situation derived from everyday occurrences in the small-screen video, and the mobile theatre installation’s metaphor of the world as a troupe on an improvised stage – are both collective self-ridicule that might rather be a long sigh of relief upon inspection.

6

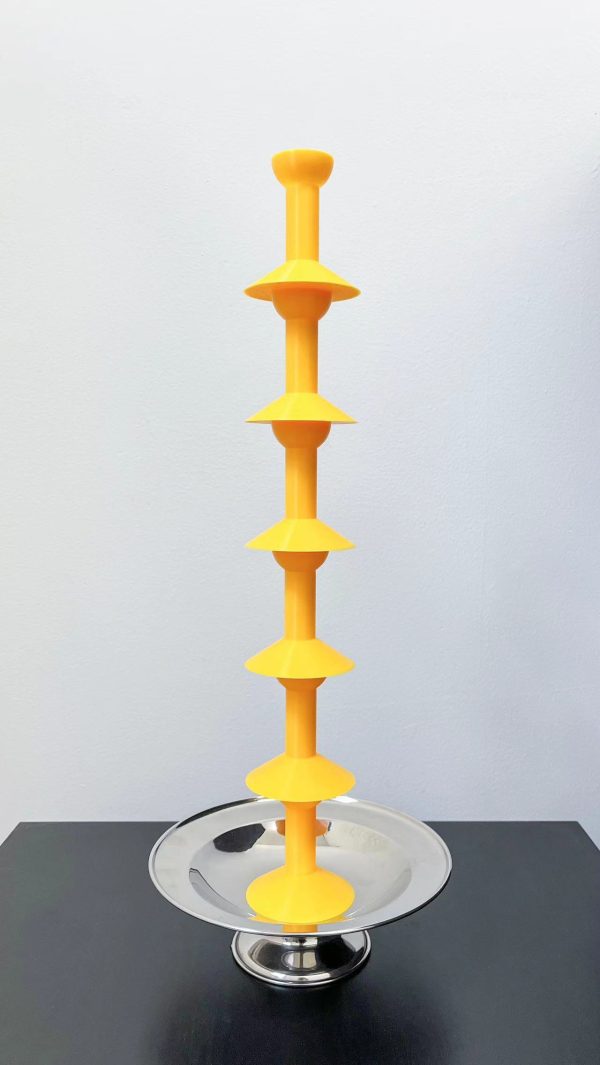

Huidi Xiang doesn’t consider herself to be living entirely in the real world. Her practice feels like an everyday walk on an assembly line, which is not industrially repetitive and plain but rather flexible and rugged like the go-kart tracks. Her work imitates and transforms readymade objects, i.e. commodities, commercial products, and decorations. The logic by which these things are fabricated is similar, but by her misplacing, reassembling, and complementing their appearance, functionality, and parts, they become alternative deviations from the logic of consumption and functionalism as vessels carrying richer emotions. The objects in Xiang’s studio are gradually assembled by the artist with a 3D printer for experimentation, where many small exercises are under lengthy observation, waiting for the moment of inclusion. Correspondingly, her box also has many different passages: the Mario shoes that no longer appear in pairs outside the petit entrance and inside the space, the classical columns formed by the stacking of glasses, etc., are all her joking triggers of alternative reflections that may differ from the established ideology.