Hive Center for Contemporary Art is pleased to announce Ren Xiaolin’s latest solo exhibition, Genyue, opening on June 28,2025, in Galleries B and C of Hive Beijing. This marks the artist’s return to Hive following his 2019 solo exhibition The BlurredEnd. The new exhibition brings more than twenty meticulously selected paintings created over the past six years. Throughan interstitial aesthetic that merges Eastern philosophy with contemporary perception, Ren reconstructs the relationshipbetween painting and the world, the individual and history—revealing a distinct visual philosophy and cultural depth. Theexhibition, curated by Xia Xiaoyan, will remain on view through August 27, 2025.

Ren has spoken of how Genyue inspired his painting practice. Genyue, the most sophisticated example of imperial gardensfrom the Song Dynasty, was established in 1117 during the seventh year of the Zhenghe reign, covering over 500,000 squaremeters and taking six years to complete. This garden-palace hybrid was conceived with emotion at its core, modeled afterlandscape painting and guided by painting theory. Its poetic and suggestive scenery was the first to embody the idea of “compressing heaven and earth into the emperor’s bosom” in imperial garden design. To Emperor Huizong, Genyue represented theentire expanse of the Chinese empire, with each miniature mountain peak carrying symbolic spatial meaning.

More than a material expression of imperial will, Genyue represents the construction of an interstitial (au milieu) space. Inphilosophical terms, “interstitial” is not a void between two entities, but a mode of existence—a refusal of fixed meaning andendpoints, a space that drifts between the natural and the artificial, order and escape, meaning and fracture. It is a site ofemergence where boundaries remain unsettled and relations unresolved. As a deliberately constructed, artificial nature, Genyue is not a preexisting paradise but a space built through labor, discipline, and ingenuity—situated in the tension betweennature and system, aesthetics and power.

What Ren draws from Genyue is not its historical imagery, but its embedded philosophy of life—where reclusion is no longer anescape, but a reconstruction through labor; where one does not seek refuge, but builds a place of habitation through action.

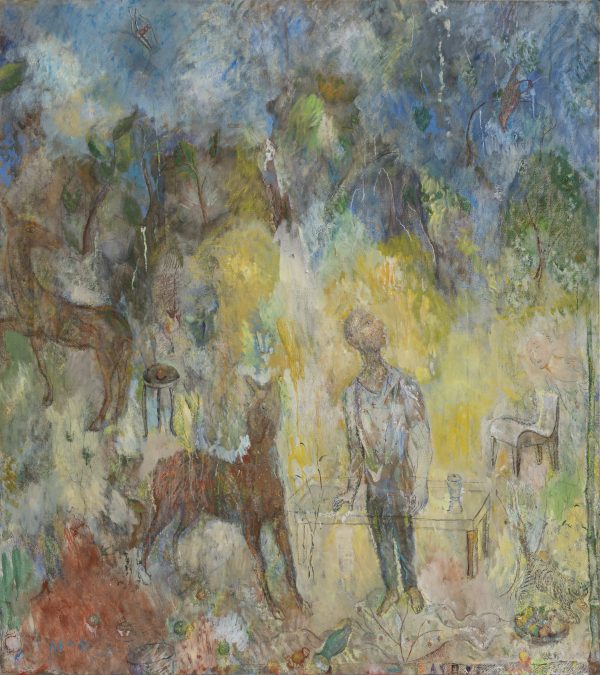

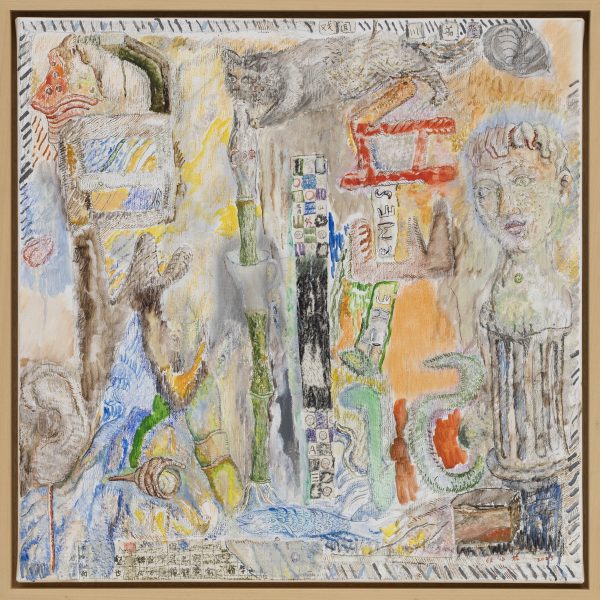

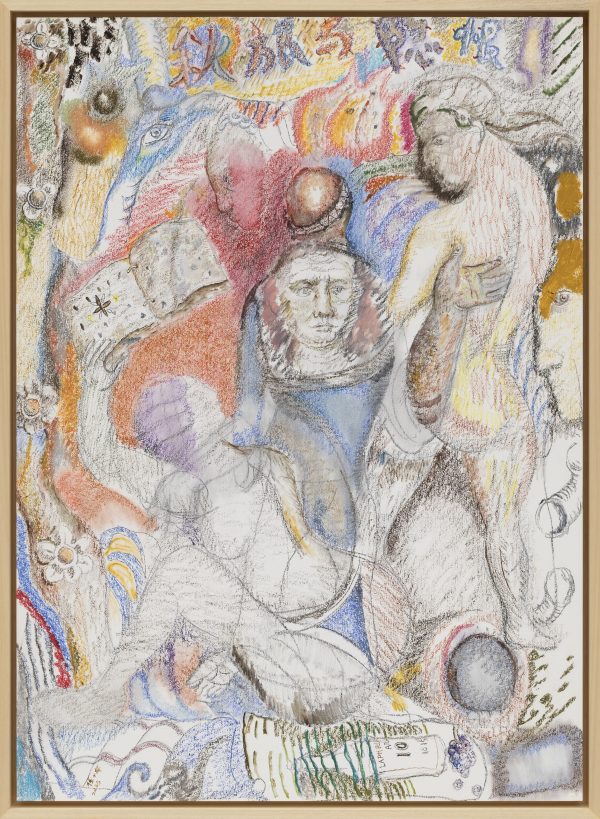

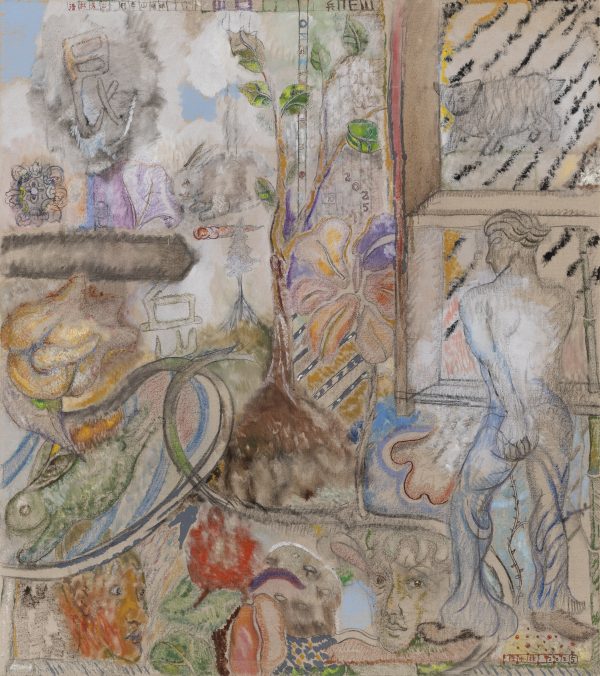

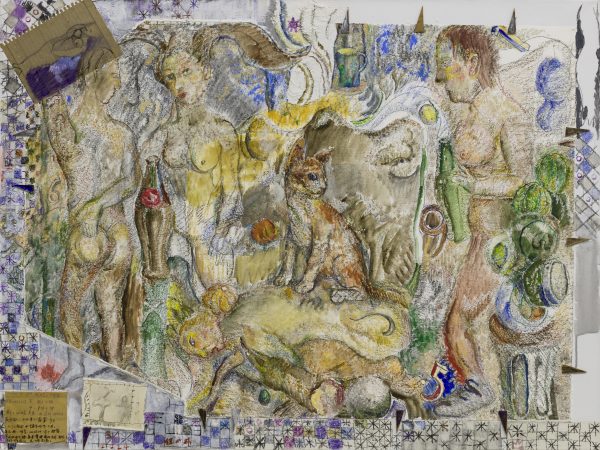

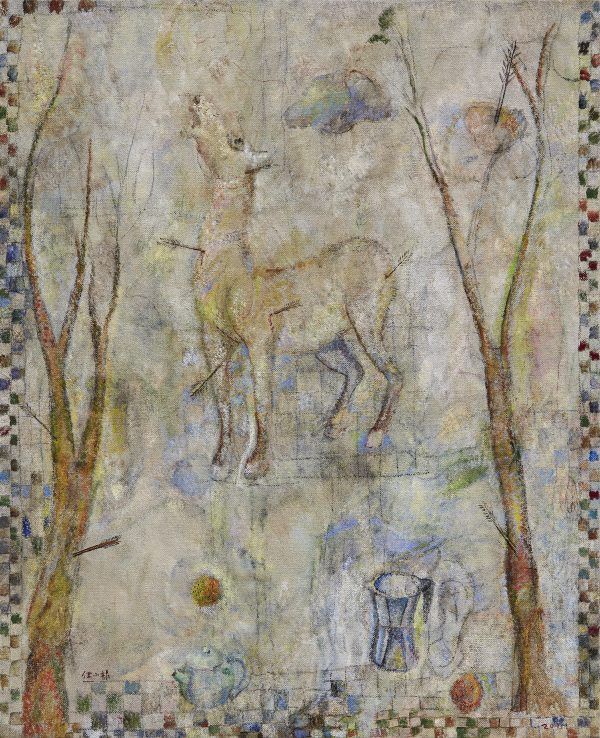

Ren’s paintings are a visual interpretation of this interstitial condition. His imagery does not belong to the tradition of ink landscape painting, nor to the logic of modernist form. Instead, it unfolds a fractured yet continuous visual structure between thetwo. Clocks, books, boots, Buddhas, Roman columns, Coca-Cola cans, miscellaneous objects, trees, and fruits coexist withinthe same space, though they seem drawn from different semantic worlds—like a dream interrupted and then sutured together.More precisely, these works do not portray one world, but place viewers in a field of tension between multiple worlds—a realmwhere time, space, and perception remain undifferentiated. This strategy of juxtaposition is not ironic collage, but a mysticalsummoning of material presence—each object carries memory and symbolism, scattered like fragments of the subconscious,waiting for viewers to weave them into meaning.

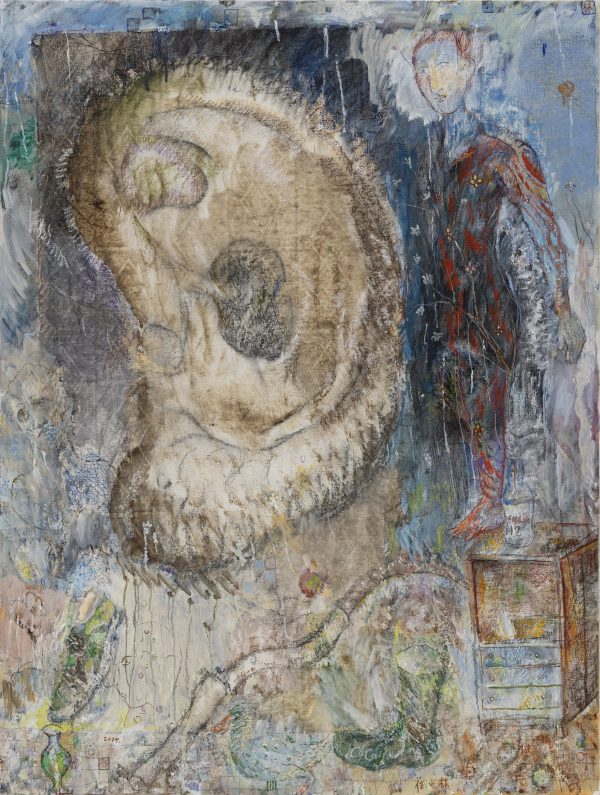

Within this logic of perception and expression, Ren has developed a distinctive painting method. He never begins with apredetermined composition. Instead, he starts with a perceived detail—an ear, a shaft of light, the edge of an object—which becomes a “center of interest.” From there, forms naturally unfold through the advance of brushwork, growing organically frompoint to field. This unplanned, uncomposed process is less a technique than a way of being: painting, observing, and thinkinghappen simultaneously. Such parallel perception reconfigures modern sensory structures, becoming a bodily enactment ofthe interstitial condition—not the depiction of a known image, but the emergence of an unknown world between perceptionand action.

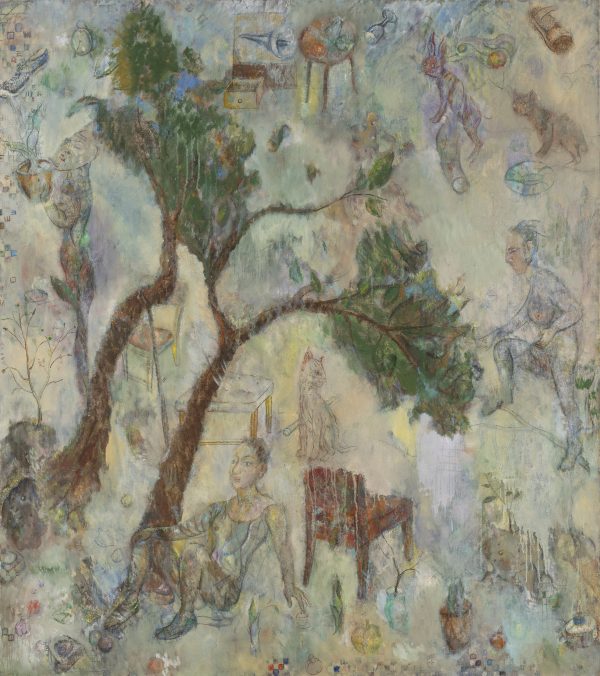

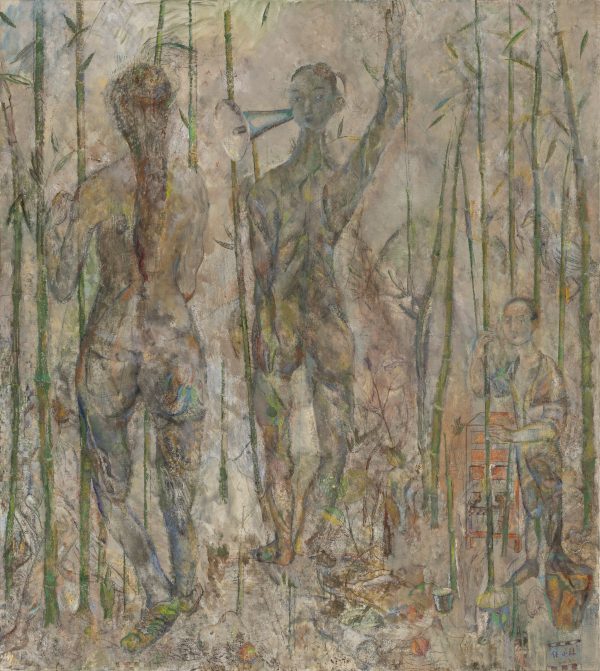

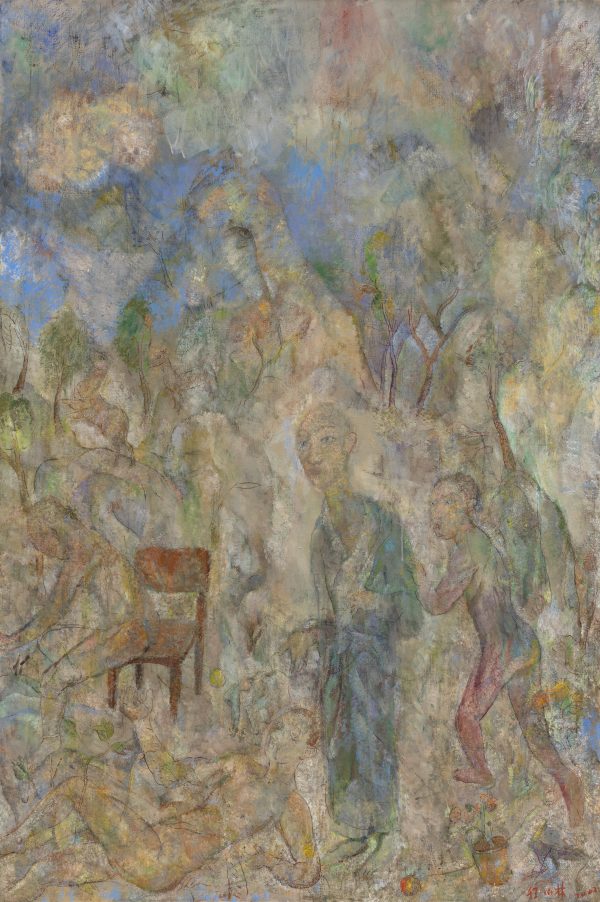

Following this acute sensitivity to the modern world, Ren exhibits a strong reclusive impulse—not an escape outward, but aretreat inward. His sanctuary becomes nature and the studio-space cherished by traditional literati. During this phase, his images retreat from representational structures of society into an aestheticized spiritual realm. The scenes become pared down:distant mountains, bamboo groves, cabinets, birds and beasts, monks and Buddhas—highly symbolic objects that togetherconstruct a classical scholar’s dwelling. The figures lose specific identity and become montages of literati archetypes—lacking individualized features but conveying a steady cultural temperament. They sit quietly, gazing ahead or in contemplation,as if drawn from an older, slower temporal dimension. These figures may not have found their true dwelling, but instead havesettled into a space that aspires to be one. This state—both escape and suspension, both retreat and not yet return—is theemotional core of Ren’s paintings at this stage.

In recent years, Ren’s compositions and formal language have grown more defined and complex. His current notion of “reclusion” is no longer a romantic return to pastoral life but a pursuit of an interstitial space between reality and ideal. He constructsa world suspended between the real and the imagined, between history and dream. The new sanctuary is not the forest or ascholar’s retreat, but Genyue—an imperial landscape engineered by the Song court. Ren has realized that just as Genyue’sartifice dismantled the ancient binary of nature and culture, the inner tensions of the self must also be lived through. The trueself must integrate with the totality of the world.

Ren’s “Eastern-ness” is not a geographic label but a visual spirit and aesthetic sensibility. Deeply influenced by Chinese traditional art—especially the structural, symbolic, and religious nature of tomb and Dunhuang murals, the line of calligraphy,and the poetic intent of literati painting—he does not treat these as subject matter but as principles of composition and perception. His lines are expressive rather than representational, pursuing the flow of qi and the organic growth of structure. Hiscompositions avoid linear perspective, instead unfolding through scattered perspectives akin to scroll painting, emphasizingtemporal movement through space. His palette is subdued and elegant, evoking the sedimented feel of ink or mineral pigmentand conjuring a sense of historical depth. These visual strategies echo Genyue—a spiritual space at once tangible and distant,artificial and transcendent.

Between tradition and modernity, East and West, reality and imagination, Ren continually reconciles, displaces, and reconfigures. He frequently uses unsaturated color tones—ash green, ivory, brick red, cobalt blue—which avoid emotional excess andtheatricality, instead generating a quiet, restrained, almost meditative viewing experience. This color language continues therefined tradition of classical Chinese painting while resonating with a modernist spirit.

Through restrained contrast, Ren emphasizes compositional relationships and rhythm. His visual rhythm is not musical but breath-like—structured by intervals ofinhalation and gaze. His paintings can be understood as multi-structuralist: fusing visual composition, perceptual psychology,cultural symbolism, and narrative logic, each painting becomes not only a visual creation but a generative spirit.

In this way, Ren’s work recalls Genyue, symbolizing a classical aesthetic mode of spatial emergence—layered, shifting, metaphorical, advancing through perception– staging a delicate game between artifice and nature, order and spirituality. Ren’spaintings extend this spiritual project: continually exploring, constructing, and deferring the possibilities of space. Like a garden designer, he lays out paths, openings, stones, and empty spaces—inviting the viewer to wander, pause, and sense. Hispaintings do not offer conclusions but portals—not certainty but a nomadic invitation to perceive.

This is the true form of the interstitial: multiple, unfinished, suspended—a space always in the process of becoming.