黄宇兴 2025

HUANG YUXING 2025

策展人 | Curator: 杨鉴 | Yang Jian

艺术家 | Artist: 黄宇兴 | Huang Yuxing

开幕时间 | Opening: 2025.9.16

展览时间 | Exhibition Dates: 2025.9.16 – 2025.10.26

地点|Venue: 蜂巢当代艺术中心 | Hive Center for Contemporary Art

地址|Address: 北京市酒仙桥路4号798艺术区E06 | E06, 798 Art District, Chaoyang District, Beijing, China

Hive Center for Contemporary Art is honored to present the solo exhibition Huang Yuxing 2025 on September 16, 2025, at Hive Beijing space.

This marks Huang Yuxing’s first gallery solo exhibition in China since 2014, and also the largest gallery exhibition of his career to date. More than thirty works will be unveiled for the very first time, including major large-scale canvases and series paintings, with several entirely new series premiering in this exhibition. All four main gallery spaces of Hive Beijing will be dedicated to the presentation.

As one of the most widely discussed and highly regarded artists in China today, Huang Yuxing was the subject of the major retrospective “Under the Vault of Heaven: Huang Yuxing” in 2023, organized by Long Museum Shanghai and co-organized by Hive Center for Contemporary Art. That exhibition offered a comprehensive survey of the artist’s practice, contextualizing Huang’s personal trajectory within shifting historical moments and highlighting how, as both an artist and an individual, he has responded to his times through self-expression and emancipation—underscoring his historical significance and artistic importance. Building on this foundation, Huang Yuxing 2025 unfolds across four chapters, each offering a distinct conceptual entry point into his current practice. Together, they present a richly layered, profoundly imaginative, and intellectually rigorous body of work. The exhibition seeks to trace the artist’s unique worldview—at once vast and intricate—through the lens of personal subjectivity, while also reflecting upon the complexity and volatility of contemporary reality. Curated by Yang Jian, curator of Hive Center for Contemporary Art, the exhibition will remain on view until October 29, 2025.

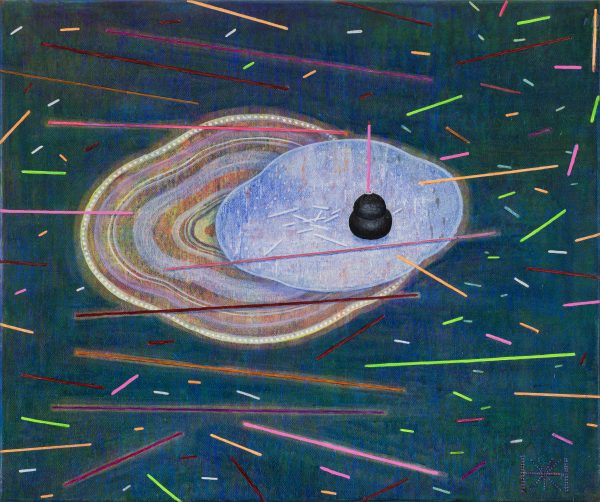

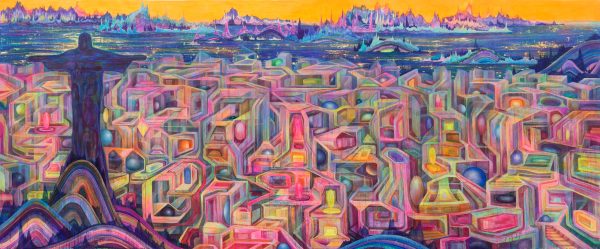

Cosmos

Beneath the radiance of “light,” scattered rays pierce hollow space; “bubbles” leap and refract as “rivers” carry them into the distance. In 2025, when we look back at more than three decades of creation through the god’s-eye view of the mountaintop statue in Light of Rio de Janeiro, we find that Huang Yuxing has never departed from the introspection of “body and spirit.” Yet his practice continually flows between the probing of energy, memory, and sites of spiritual dwelling, and the poetic contemplation of subjects beyond the social and the human—civilization, nature, and the cosmos. From faintly glowing bubbles to the vastness of interstellar space, Huang’s imagery drifts seamlessly, perhaps because in his worldview, they are one and the same.

As the first chapter, or a kind of prologue, Cosmos presents itself more as an “overture.” It both lays out the viewer’s visual expectations and sets a meditative rhythm, allowing one to reconstruct perceptions of time and existence through the triple structure of “object, painting, and universe.” Whether the universe is autonomous, the position of the individual within it, and the power relations between civilization and nature are all posed silently within the visual narration. From the Eastern cosmology of “the Way follows nature (道法自然)” to the “biopolitics” of modern philosophy, after years of practice, Huang Yuxing seems to have enacted again and again a dual summons of “cosmos and self.” As viewers, we are invited to enter a vast visual structure, while also being encouraged to seek our own position within the polyphonic narration of time, light, color, and energy—to realize, in the contemplative experience of the game designed by Huang Yuxing, a “universe created by the viewer.”

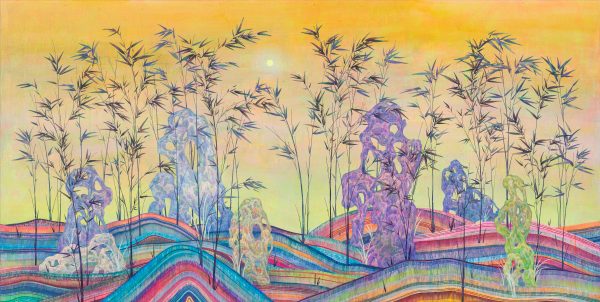

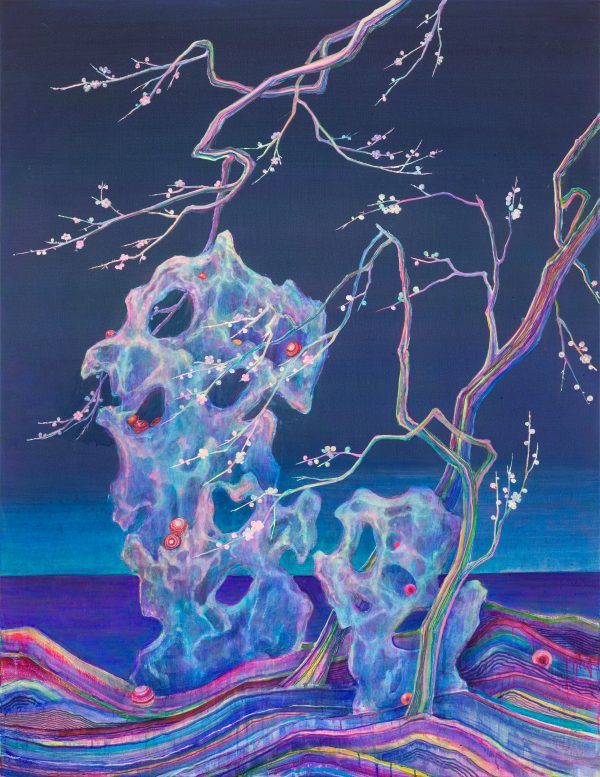

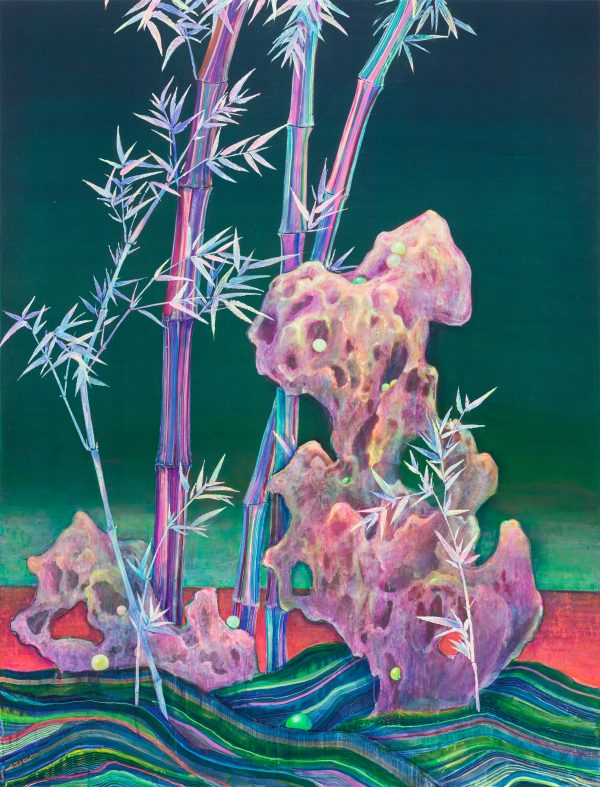

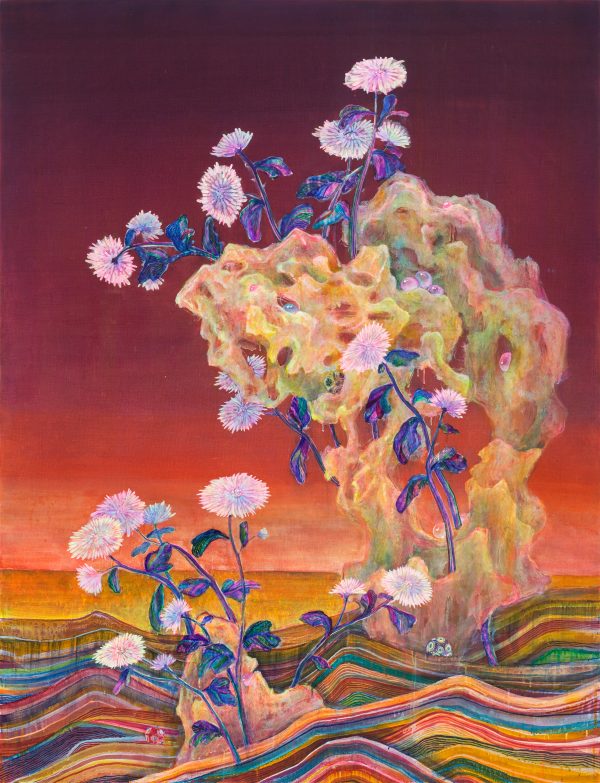

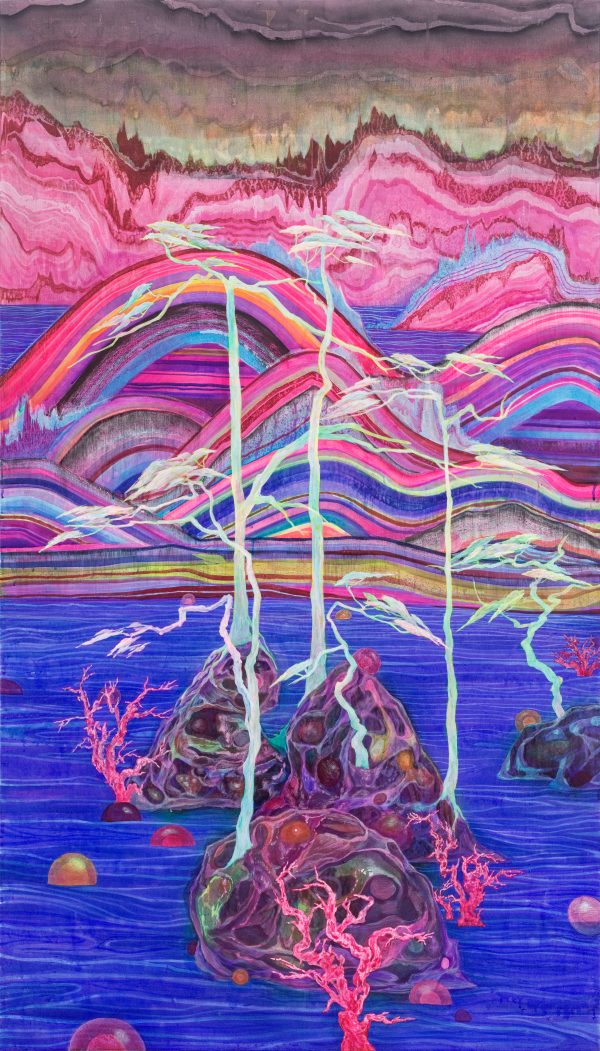

Toward Elsewhere

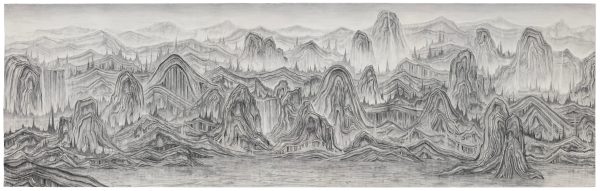

This chapter focuses on Huang’s longstanding dialogue with “landscape” and “garden” as civilizational schemas and cosmic metaphors. From the contemporary reinterpretation of garden vocabularies such as artificial rockeries, to the reimagining of traditional landscape motifs like plum, orchid, bamboo, and chrysanthemum, Huang’s landscapes are neither realist nor nostalgic. Instead, they construct a “landscape consciousness” embedded within contemporary experience. What he is concerned with is not the outward appearance of mountains and rivers, but their very mode of existence as experiential structures, emotional archetypes, and vessels of spirit—at once symbols of civilization and echoes of nature, condensations of historical memory and reflections of individual awareness.

Thus, Toward Elsewhere is not a departure of the body but a drift of consciousness. It is not the act of entering the forest, but of being drawn by its shadow—passing beneath the surface of reality to reach a “mental terrain” that is both tangible and indeterminate. In this heterogenous space constructed by images, “seeing landscape” is no longer the appreciation of an external scene, but a gaze directed at the boundaries of inner existence. It touches the suppressed edges of perception, the undercurrents of consciousness being stirred. Here, “landscape” ceases to be an object of view, and becomes instead an experience: a perceptual field at the boundary of civilization, a visualized meditation. It invites us to transform “looking” into a mode of “being present,” to rediscover within the fluid order of images the obscured connections between self and world.

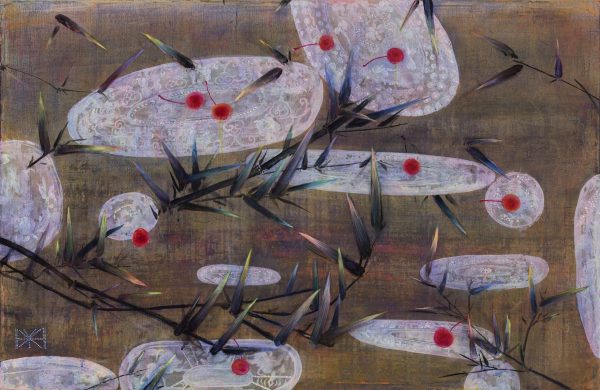

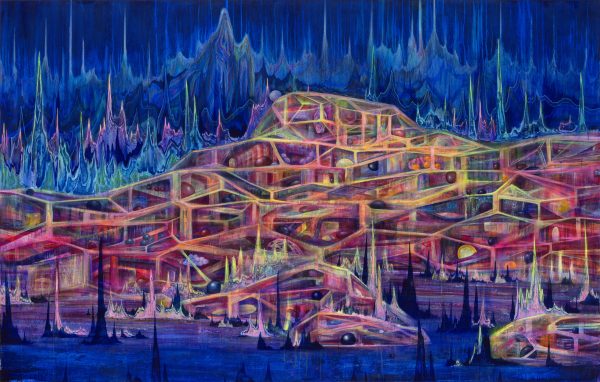

Ontologies of Matter

If the Rivers and Mountains series opened a macrocosmic narrative dimension, Huang’s recent still lifes embody his turn to the microcosm—to the rhythms of material life. Fables of Matter gathers images of bubbles, crystals, minerals, sealed vessels, and drifting particles—seemingly static fragments that nonetheless brim with latent vitality. These perceptual shards, surfacing from the depths of consciousness, reflect Huang’s ongoing inquiry into the spatialization of energy and the materialization of memory, while also revealing his sensitivity to the generative currents of daily life and his plain affection for surrounding people and objects.

This chapter raises questions about the relationship between matter and perception, image and consciousness, body and memory. Do objects feel? Are images self-sufficient? Can we glimpse, within the temporal ripples of still life, a form of life suspended between fragmentation and growth? Huang constructs connective channels between inner and outer worlds, turning painting into a mediator between form and sensation, personal experience and regenerative order. These works capture the tremors between ordinary existence and painterly thought—and painting, for Huang, is the only language capable of seizing, preserving, and transmitting such tremors.

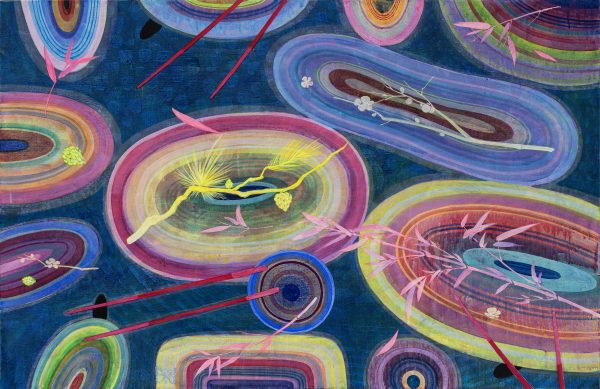

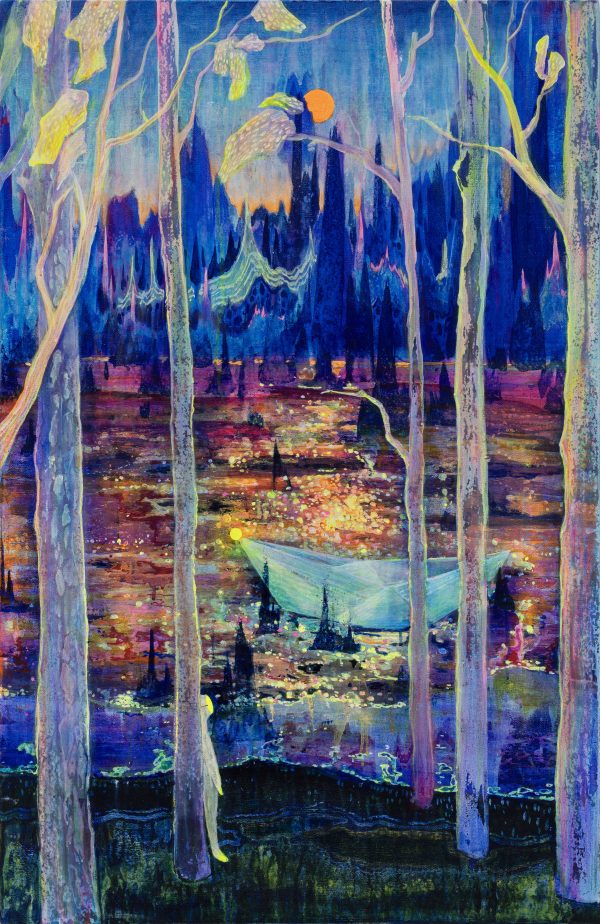

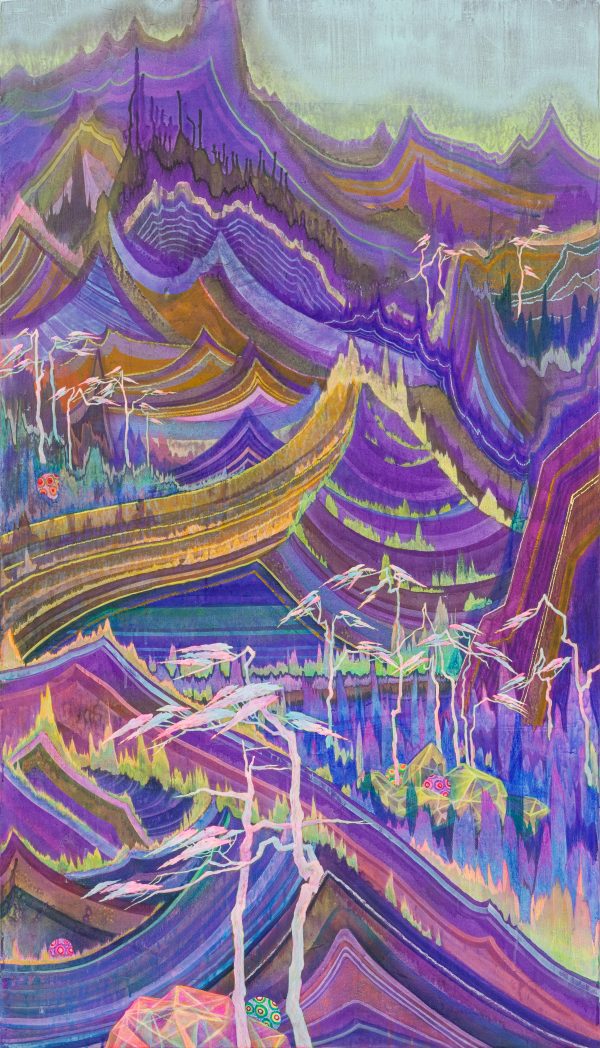

Entanglements of Walden

In Henry David Thoreau’s Walden, the lake is not only nature but also a mirror of self and society, time and solitude. The title Entanglements of Walden seeks both to establish a poetic link between Thoreau’s lakeside meditation and the shifting water-edge imagery in Huang’s paintings, and to translate that meditative impulse into a contemporary experience of “drifting at the boundary.” In this chapter, water, architecture, and tree shadows weave unstable borderlands—neither pure nature nor solid civilization, but visual fault lines that drift among time, memory, and perception. Works such as Walden simulate states of psychic suspension through layered colors and interlaced lines: as though the viewer is not standing before the painting, but gazing from beneath the water, from within a dream, or from a nocturnal rain into the threshold form of civilization.

Here, Entanglements of Walden emerges as a dreamlike reflection of civilization. Nature can no longer be restored to origin; youthful imagination can no longer reconcile with reality. Yet in the fissures where the two overlap and erode one another, a new perceptual mode quietly arises—not a utopian promise, but a site where new consciousness sprouts upon ruins. It may read as a romantic return to nature, or as a philosophical vision born of civilizational crisis. Between the echoes of civilization and the reflections of nature, can we still hear the faint resonance of our own existence? Can we discern the coordinates of contemporary spirit within veils of color and warped structures? Huang Yuxing’s work offers neither answer nor allegory, but rather a question articulated through painting itself—a modest, classical, and inefficacious medium that nonetheless insists on questioning.