Hive Center for Contemporary Art is pleased to announce the group exhibition Grace Period will open on August 9, 2025 at Hive Becoming Shanghai. Curated by Chan YuYing, the exhibition brings together over a dozen works by four artists—SHUM Kwan Yi, Wu Haifeng, Xiong Wei, and Zhang Jialei—each exploring the formation of provisional order at the edges of existing systems. Grace Period focuses on a liminal state in which structures have not yet taken hold, a momentary gap born of absence, delay, or non-participation, wherein the subject temporarily eludes discipline and classification. The exhibition seeks to capture the images, species, and perceptual modes that emerge from this suspended moment, and to trace how each artist carves out heterotopias within a space not yet governed by syntax. The exhibition will remain on view through September 16, 2025.

Grace Period is a temporal threshold in which the subject is momentarily exempt from the grip of structure. It is not a pardon, but a time before inclusion—a space prior to being folded into the structure. This condition is rarely the result of active choice; more often, it emerges from marginality, absence, or a lack of fluency in the syntax of one’s surroundings. The exhibition begins in a delayed moment—a pause in which structure has yet to assert itself. Syntax breaks down, rules remain suspended, and naming has not yet taken place. In this suspended state, we momentarily exit the world’s systems of categorization, existing in a weightless position not yet fixed or defined. Before structure arrives, before naming begins, we are briefly granted a kind of exemption—light, unanchored, and unclaimed.

It is a membrane woven from delay and unknowing—one that allows us to hover outside the pull of external order, momentarily exempt from capture, discipline, and classification. Grace is not a void, but a contingent interval: a space in which the subject has not yet been absorbed into the system, and in which one may grow, observe, hesitate, or even transgress. It may mark the position of the uninformed outsider—or, just as often, a shelter deliberately constructed by the knowing—a micro-order carved out to suspend breath.

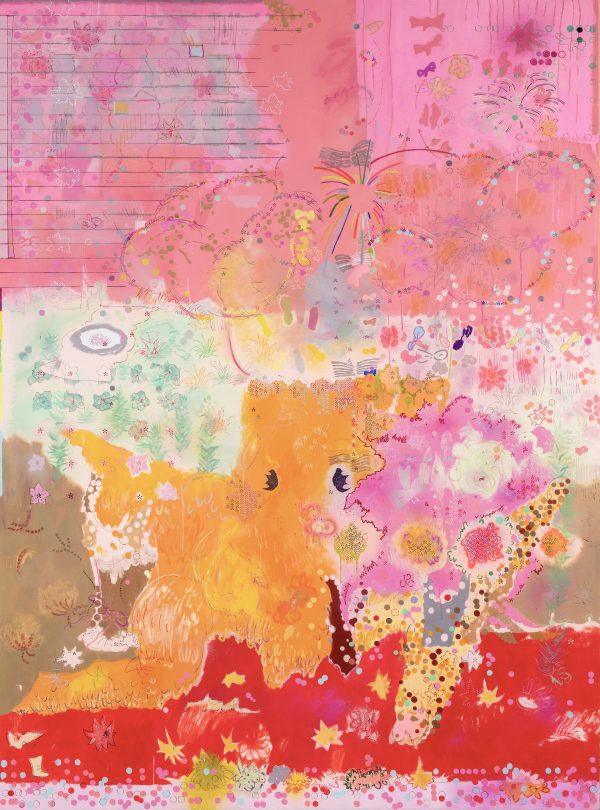

The works in this exhibition respond precisely to those moments when syntax fails: from still images in which structure has yet to take effect, to the nameless expansion of peripheral others, and finally to subtle divergences unfolding within language itself. Xiong Wei’s sculptural works present a range of non-native species—relocated by human hands, accompanied by economic expectations, yet indifferent to local rules. They grow, cross boundaries, and generate their own orders. Crayfish, tilapia, apple snails, and bamboo—these heterogenous life forms penetrate established contexts and build fleeting zones of prosperity beyond grammar, until rule-bearing agents arrive to impose structure and limits. Zhang Jialei composes unruly gardens through the rhythm of her own gestures. In her images, symbols break away from the score of structure, as if exploring an alternative syntax within sentences not yet pinned down by punctuation. She does not reject order; rather, she constructs a membrane of her own, through which an inner tempo begins to unfold. In Wu Haifeng’s paintings, time seems suspended and space hollowed out—people and objects float like words adrift in an atmosphere yet to be grasped. The three musicians appear isolated, yet resonate: immersed in their own sonic worlds, they remain silent toward one another, but share a quiet synchronicity through fluid perception. Here, relation does not depend on predetermined structure—it arises naturally, within air not yet settled. SHUM Kwan Yi’s “caves” form another domain of grace: landscapes become self-contained reflections of psychological states. The shifting scenery between cave openings signals the drift of consciousness; in her paintings, she constructs a semi-sealed, semantically charged system—a self-authored grammar that momentarily fends off the incursion of structure.

These artists open caves to inhabit and gardens to recalibrate—not as acts of withdrawal, but as a means of reconfiguring the rhythm of breath, composing spaces of self-directed growth within airless regimes. They enact what might be called “heterotopias within structure”. These works do not seek utopian escape, but dwell, repair, and re-encode from within; when the path is already drawn, we move through it with flexibility, temporariness, and tactical improvisation—borrowing, smuggling, and subtly reworking another’s grammar.

In the interval before names, the cave knew no intrusion, the species no law.