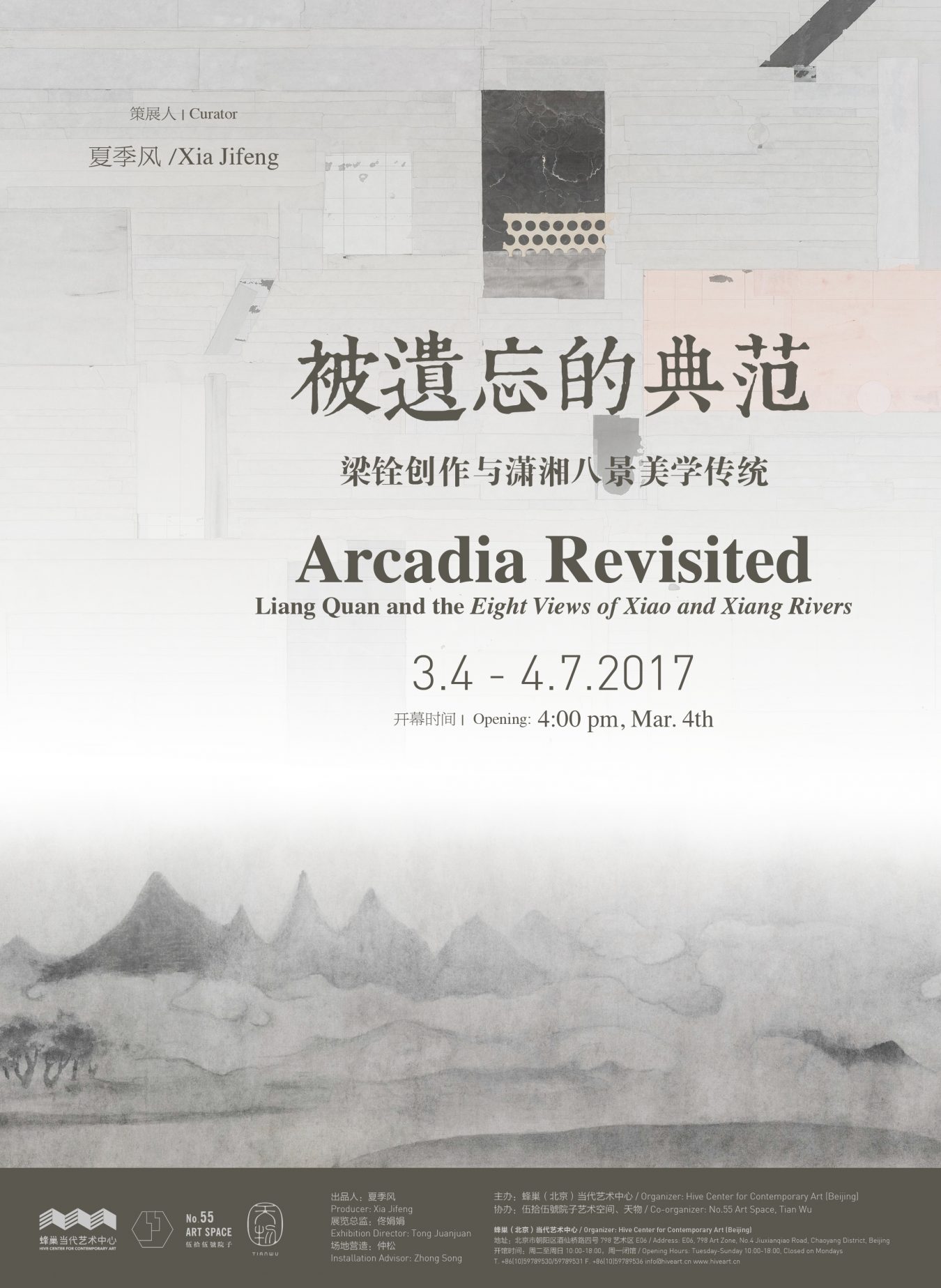

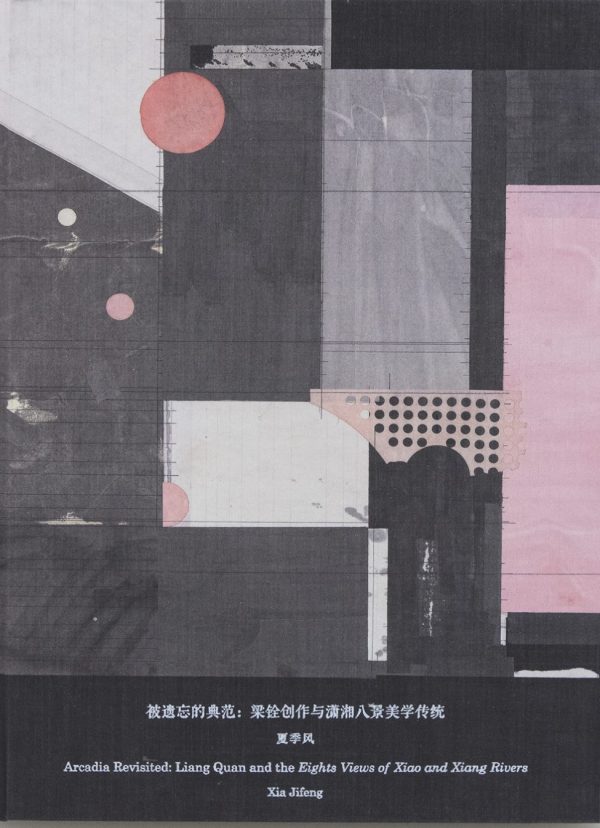

Hive Center for Contemporary Art (Beijing) is pleased to announce our first exhibition in 2017 , Arcadia Revisited: Liang Quan and the Eight Views of Xiao and Xiang Rivers. As an significant artist of Hive Center, Liang Quan has had several shows in our space, such as Folds of the Infra-fade: On the Ink Works of Liang Quan (2013), Amassing The Essence: Thirth Years of Painting by Liang Quan (2015) and other important solo exhibitions. At this time, the artist will bring his latest Xiaoxiang-themed creations, presents the relationship between traditional aesthetics and contemporary art, and the influence of traditional visual model on contemporary art, and has a deep discussion on the possibility of an unique artistic path and the exploration of future art making. The exhibition is curated by Xia Jifeng, organized by Hive Center for Contemporary Art, co-organized by No. 55 Art Space and Tian Wu, the space scene is designed by Zhong Song. This exhibition will open from March 4th until April 7.

Born in 1948, Liang Quan is the one of the first Chinese contemporary artists who studied in America after Chinese Cultural Revolution. Also he is one of the first Chinese artist who have engaged in abstract works. The utilization of the rhetoric of dual East-West cultural heritage and intertextuality became the crux of establishment of Liang’s artistic style. This exhibition will show Liang’s contribution and practice in translating the Western Abstract language to the East using Liang’s masterpieces from different phases.

The well-known Chinese traditional cultural imagery of “Xiaoxiang” has its original semantic roots as a literary concept. Though literary references date back to the Pre-Qin era (21st century BC to 221 BC), the terms “Xiao” and “Xiang” were first combined during the Wei and Jin period (222–589 AD). In painting, the Xiaoxiang schema emerged after the literary term was defined. It would not be until the Tang dynasty (618-907) that verifiable instances of shanshui landscape paintings titled “Xiaoxiang” would appear. The Xiaoxiang imagery of this period was mostly rooted in the legend of “Emperor Shun’s two concubines,” Qu Yuan’s ci poetry, and exile literature. It came to coincide with yearning for paradise and ideas of mental purification through distant wandering, and was then mixed with notions of nostalgia, and the imagery of the contented “hermit fisherman.” The first true instance of a painting titled “Eight Scenes of Xiaoxiang” is described in the Dream Pool Essays by Song dynasty writer Shen Kuo (1031-1095). For nearly a thousand years since, the Eight Scenes of Xiaoxiang have remained an enduring theme among painters from all eras, and it has spread across a wide territory, from China to Japan, Korea and all of East Asia to become an eternal artistic motif. In Japan, with its similar climate to China’s Jiangnan region, the development of ink painting was intimately linked to Zen hermitage culture. Artists there were naturally receptive to the Jiangnan styles of Dong Yuan, Ma Yuan, Xia Gui, Muxi and Yu Jian, and their formal vocabulary came to form the creative mainstream. Artists on the Korean peninsula felt affinity for cold, sparse landscapes. They modeled their Xiaoxiang themes around the cold forest styles of such northern Chinese artists as Li Cheng and Guo Xi. Locally, in China, Xiaoxiang-themed creations fused these two different stylistic traits.

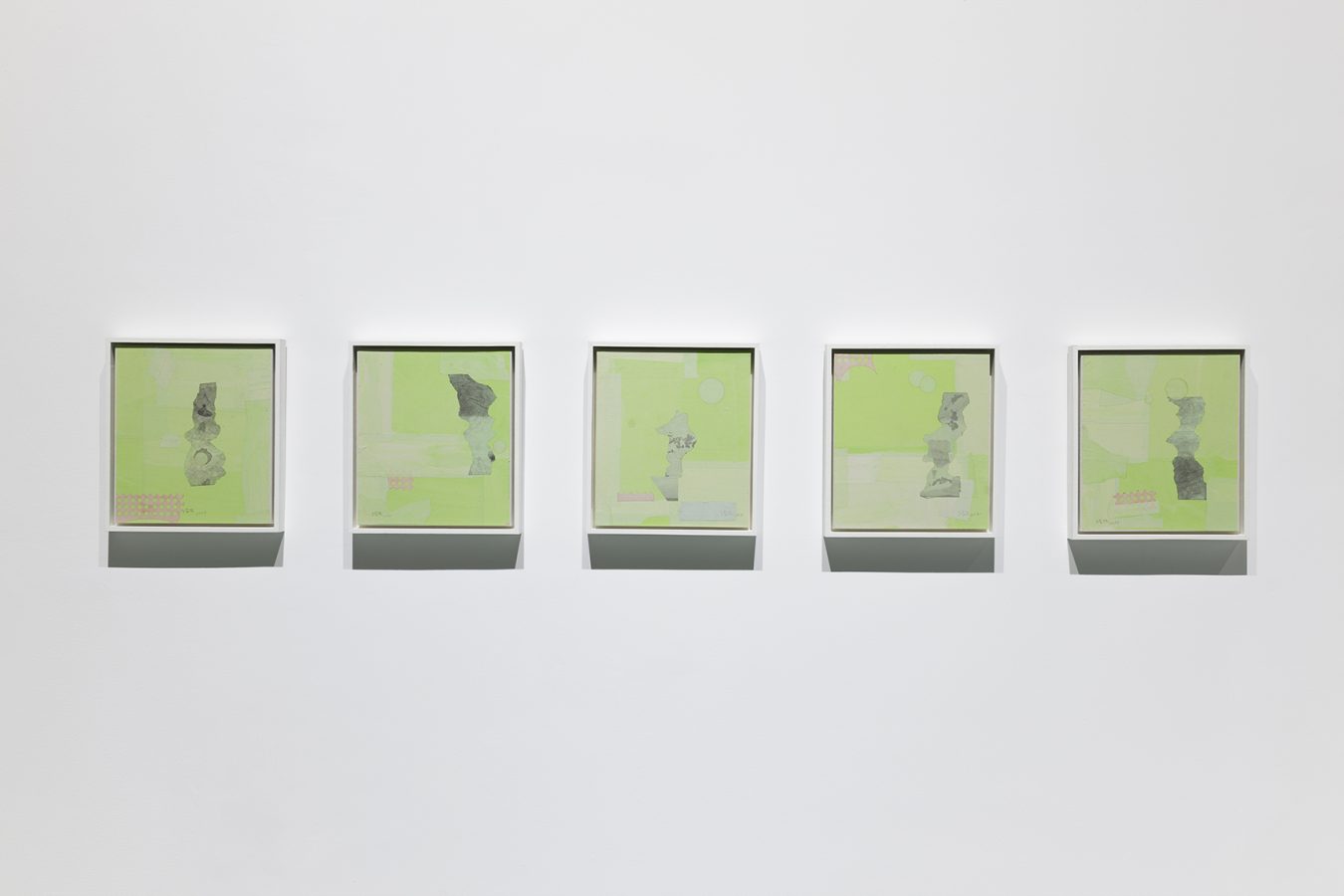

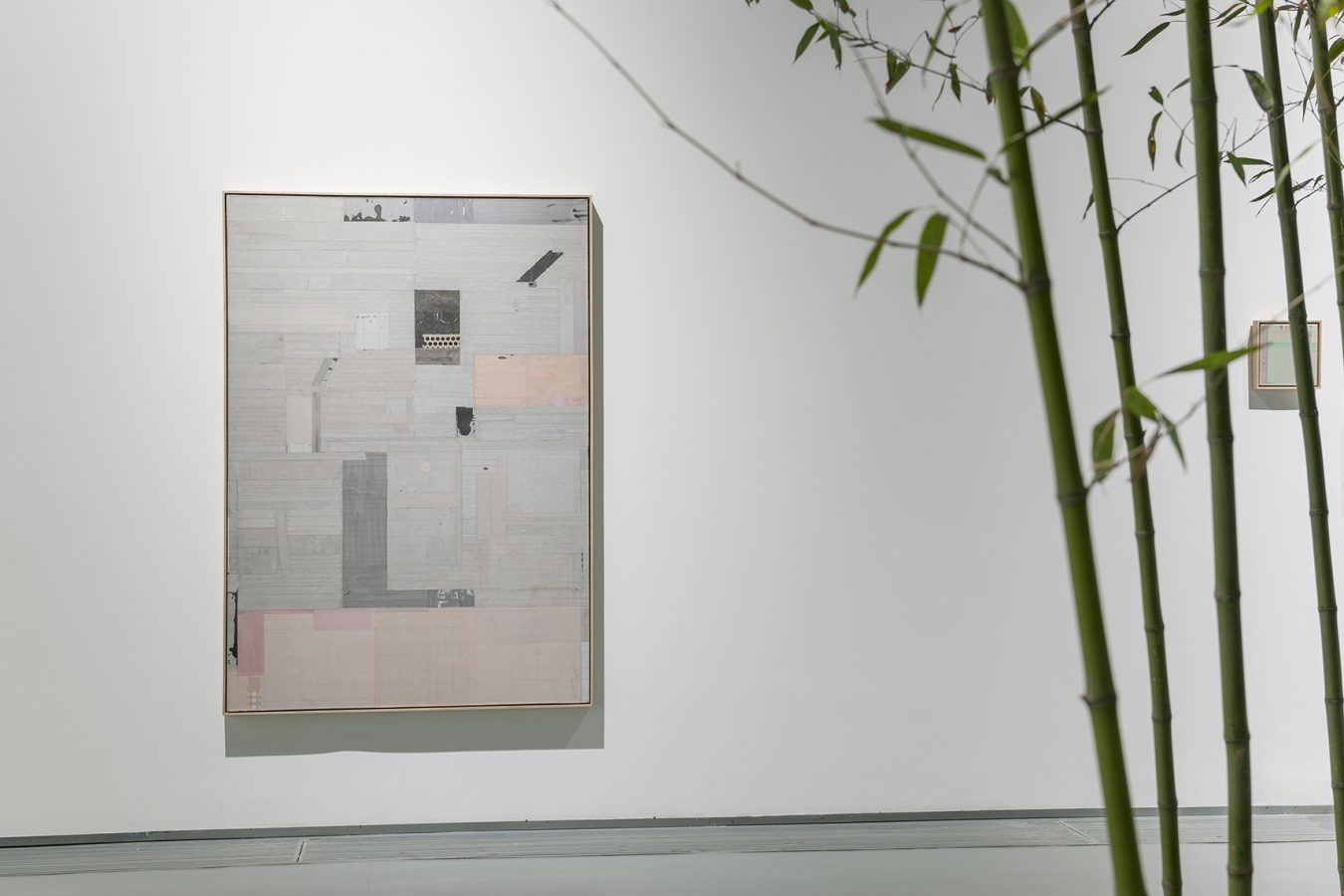

Liang Quan’s Xiaoxiang-themed creations are rooted in his individual aesthetic cultivation, his grasp of Zen culture, and his deep understanding of this creative theme. When all of this encounters an international painting language, a uniquely styled schema is born. Like the majority of those who came before him, Liang Quan has never visited the birthplace of the Eight Scenes of Xiaoxiang in person; he has only vicariously entered into this creative context. The goal of conveying the Eight Scenes of Xiaoxiang is to fix moist air and flickering light onto the painting. It is unconnected to the referenced region, but it is connected to seasonal climates and fixed times, and most importantly, it is connected to the mindset of the artist. This is cultural imagery that lives eternal in the hearts of literati through the ages, as well as a movable landscape. The “localization” and “abstracted” aspects of the Eight Scenes of Xiaoxiang echo Liang Quan’s own abstract creative form. They come together to form a resonating schema.

In Liang Quan’s Eight Scenes of Xiaoxiang series, those ancient landscapes we can never see in person, through the individualized understanding and transformation of the artist, have come to transcend pure visual experience to take on an inner mental landscape with universal meaning. The infinitely repeated chants and writings, joys and sorrows of literati painters through history become perceptive experiences of the past that repeatedly reemerge in the artist’s mind and coalesce into an unbreakable aesthetic heritage. American sinologist Max Loehr describes Ming and Qing dynasty painting as “art historical art.” This term seems to have a slightly negative connotation, implying that artistic innovation has been confined within a framework of existing art. Liang Quan may be working in the same traditional format of the Eight Scenes of Xiaoxiang, but his approach is entirely different from the model of imitating old paintings. He activates tradition through contemporary artistic ideas and forms, and thus gives rise to an unprecedented new spectacle and language in an attempt to present an Eastern height to contemporary art.