Liu Qi, born in 1979, is a young artist who has carried on tradition and demonstrated remarkable ability. He uses ink methods to create his paintings, but he is not confined by the time-honored rules of this ancient tradition. In his works, a method of dividing color fields with lines has replaced the freehand and gongbi techniques often seen in Chinese ink painting—these techniques are well-developed in his works, but his unique modeling and colors are what leave the strongest impression. He models the human form in a virtually flat manner with its roots in the sculptures and mural paintings of both East and West. His colors are direct and pure, almost as if we can find aesthetical counterparts and visual comfort within the levels of sociology and cultural anthropology. Looking over Chen Qi’s work, it seems that he has been consciously striving to peel away the professional techniques he accumulated through his rigorous academy training and cast off the standard painting experience in order to bring his creations closer to an instinctual aesthetic experience. For the artist, this is a personal insight, as well as a historical awareness that T. S. Eliot described as involving “a perception, not only of the pastness of the past, but of its presence.” This awareness gives the artist not only his own unique qualities, but a historic background in which an entire artistic tradition exists simultaneously.

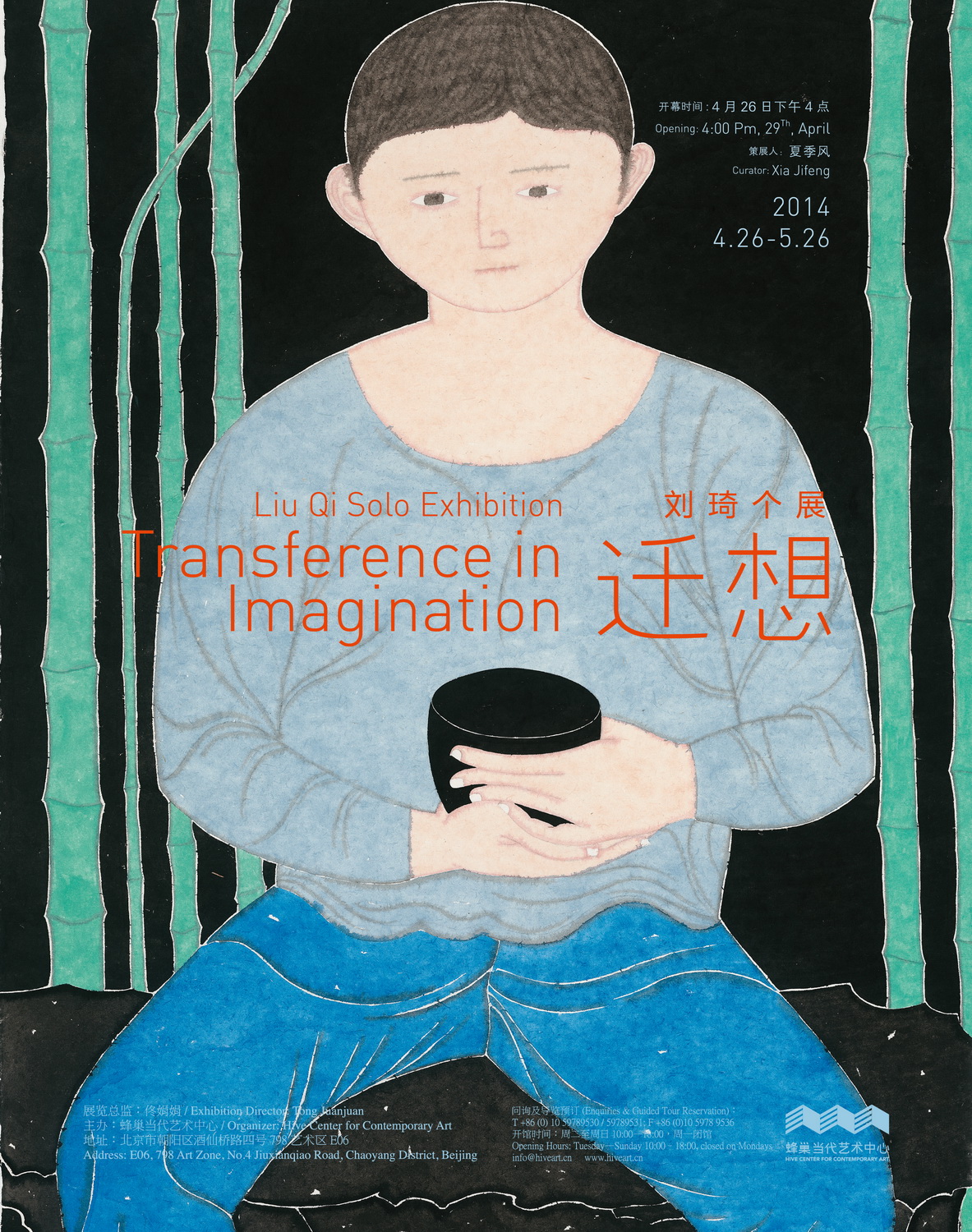

The term “transference in imagination” in this exhibition’s title is derived from a theory of painting advocated by Gu Kaizhi during the Eastern Jin dynasty. “Transference in imagination” is a cause, a beginning, describing the actions of the artist’s imagination during the creative process. The result is “inflected reception,” the transference of subjective ideas onto objective objects. It is the same with the success or failure of a work of art. Strictly speaking, only through the artist’s “transplanted thoughts” and the viewer’s “inflected reception” can mutual understanding and perception be deemed complete.