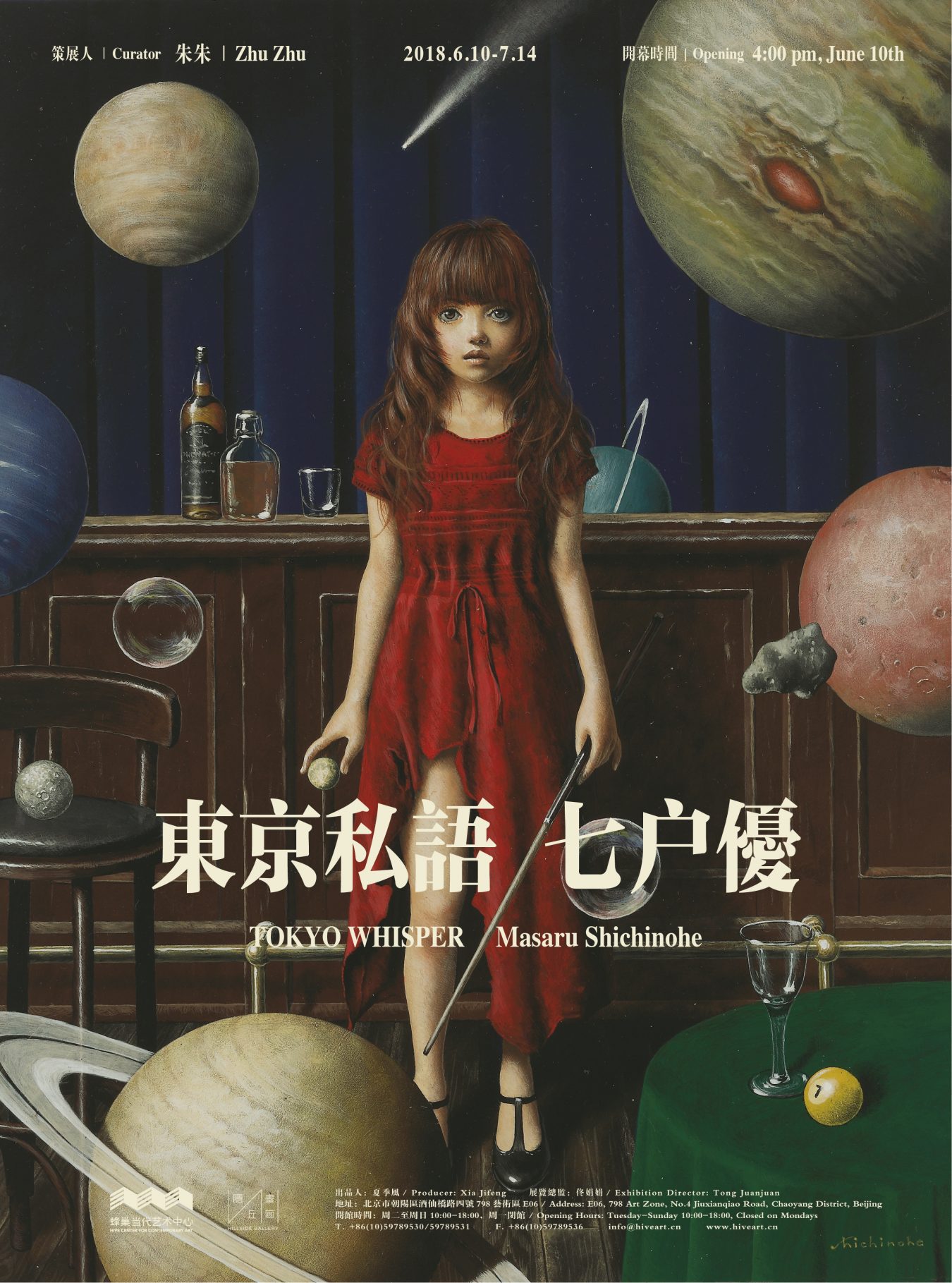

Hive Center for Contemporary Art (Beijing) is honored to pronounce that Masaru Shichinohe’s first exhibition in China “Tokyo Whisper” will be presented at the main hall from Jun.10 to Jul. 14, 2018. Curated by Zhuzhu, the exhibition will mainly show the works of recent years by Masaru Shichinohe, some representative works of his different creating periods from 1990 will also be covered in the show. Jointly hosted by Hive Center and Hillside Gallery, the exhibition will be last until Jul. 14, 2018.

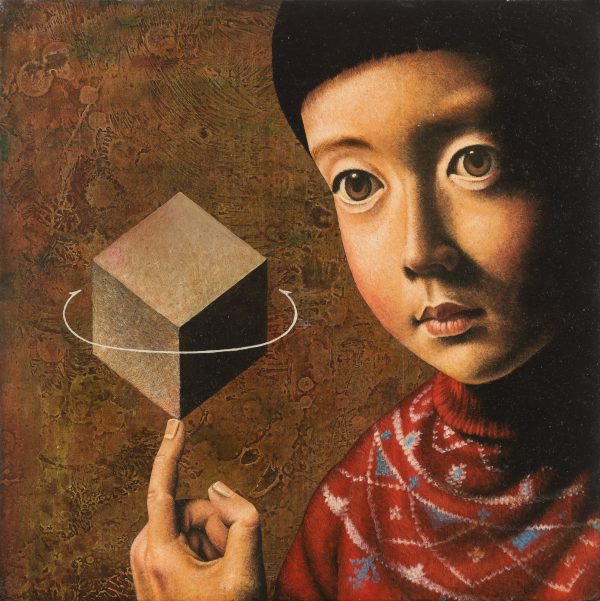

Masaru Shichinohe, born in 1959 in Aomori Prefecture, Japan. He graduated from Musashino Art University, College of Art and Design, major in architecture. After working in architectural firm for three years, he started his career as professional painter. The atmospheric pressure on Masaru Shichinohe’s planet also approaches zero. Apalpable stillness pervades his tableaus of young boys and girls, glassy-eyed rabbits, mechanical baubles, celestial bodies, led zeppelinds, and clocks eternally set at 12 o’clock. Even demonstrations of movement like the trajectory of a billiard ball are stopped in mid-air at different points in t, recalling the Italian Futurists’ experimentations with multiple exposure photography. They are stutters in Shichinohe’s otherwitse frictionless space.

The post-war Japan Masaru Shichinohe experienced was rising through rapid economic growth, and by the 1980s, everything was highly ordered. As he says, “There was nothing to fight against.” He set aside his avant-garde views and aspirations to change society, and turned to the creation of a space for “whispers,” in a trajectory that in some way resembles the transition from the Meiji to the Taisho. Of course, different eras have different experiences and expressions, and on Shichinohe’s channel, these whispers or private narratives do not use the first person, but are instead retold through the object of the doll.

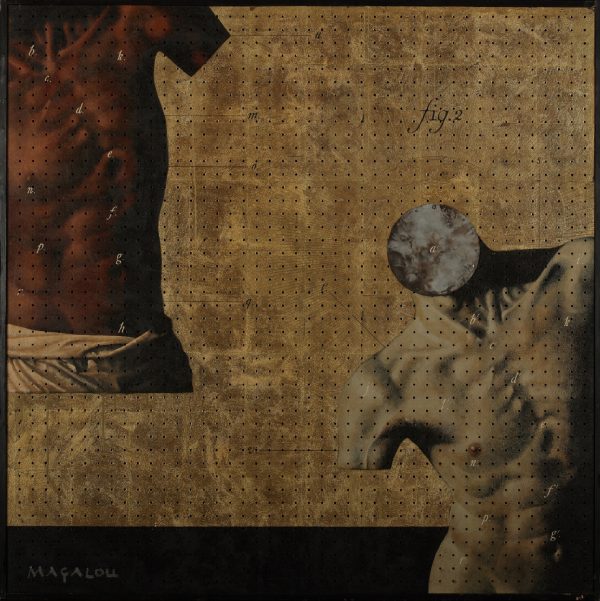

It is difficult to crack the secrets of a culture’s aesthetic psychology from the outside, secrets such as why dolls, specifically child dolls, are something of a collective obsession in Japan. Shinʼya Tabuchi may be able to provide an explanation. In his book Chance Meeting on a Dissecting Table of a Sewing Machine and an Umbrella,[Shinʼya Tabuchi, Chance Meeting on a Dissecting Table of a Sewing Machine and an Umbrella, Jin Jing, trans., Chongqing University Press, 2014.] he traces back through the works of such artists as Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, Théodore Géricault, and Hans Bellmer[Hans Bellmer (1901–1975) invented ball-jointed dolls that were immensely influential in Japan. Masaru Shichinohe loves this invention, and identifies with his anti-Nazi aesthetic ideas.] to show that mechanical forms are an extremely important facet of modern art. He channels André Breton, saying, “Nineteenth century people were transfixed by ruins, while twentieth century humanity was moved by ‘model dolls.’” In my understanding, this is about emotional transference. In the mechanical civilization society, people’s roles are also highly mechanized, their sense of history lost, the complexity of human nature flattened and obliterated. Furthermore, compared to life, fleeting as a cherry blossom, the doll can resist the decline and death of maturity, and be like a cherry blossom eternally blooming on a painted screen. Perhaps uniquely sensitive to this, the Japanese discovered a mirror-like self in dolls, and went on to magnify and strengthen this facet of modern art.

In any case, this has become something of a tradition, with many artists projecting themselves onto them to carry out differentiating individual encoding. Masaru Shichinohe’s creations can be placed in this thread. When I asked him about his views on Yoshitomo Nara, he jokingly responded that every time he sees Nara’s art, he wonders “How he can still be painting the same girl; isn’t he tired?” But then he realizes, “Aren’t I still painting the same girl?”

The image of Masaru Shichinohe’s girl comes from the American brand Mentholatum Ointment. Before this, the formation of his self-consciousness was influenced by author Taruho Inagaki,[Taruho Inagaki, unfamiliar to most of us, believed the artificial was greater than nature. He famously said that glass beats diamond. He created a “nonsense literature” in Japan that describes the wonders of ordinary life in short, polished vignettes. His protagonists were all children.] and he painted images of boys. Aside from Inagaki, other literary influences should include Lewis Carroll, author of Alice in Wonderland, and science-fiction novelist Jules Verne, as well as Western Medieval astrologers. Shichinohe once produced a coloring book titled The Box Children, and his boy series could be said to be a continuation of its themes: the boy is in a semi-confined state, as if as a means of maintaining childlike innocence, wallowing in the instincts for imagination and play. He created for himself a stage to replace reality not unlike Alice’s Wonderland, not an entirely self-sufficient dream, but a metaphorical satire of the real world and exploration of the mysteries of the universe replete with mournful, helpless self-examination. Even when the main character became a girl, this theme and tone remained unchanged.

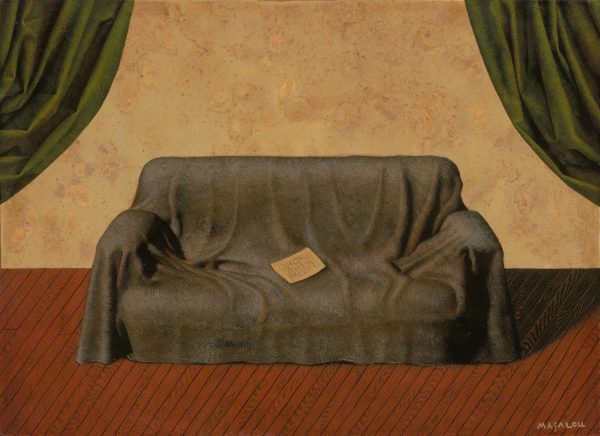

The little nurse in the Mentholatum Ointment logo was originally holding a box of medicine in her hand, but Shichinohe replaced it with a handgun, with what may be anti-colonial tones. In later works, the girl became increasingly Japanified, or perhaps increasingly Shichinohified. Like a geisha’s costume-change performance, this girl appears variously in mutilated form, as a bystander with a camera, as a Lolita leaning back on a sofa or hairdresser’s stool, or as Princess Kaguya on the moon[For the Japanese folklore persona of Princess Kaguya, see Hayao Kawai, The Folklore and Psyche of Japan, Fan Zuoshen, trans., Sanlian Bookstore, 2007. The fifth chapter describes how she turned down marriage proposals and moved to the moon, representing the Japanese image of the “eternal girl.”]… Shichinohe has constantly revised and redefined this image, bringing it closer to the doll in his heart. As time passed, he was no longer satisfied with this intertext, and produced his own doll, giving her a name no one else could be privy to. That exclusivity seems to have grown by the day. His friend, novelist Ichi Orihara, said he had told him “He gets embarrassed when he changes her clothes for her.”[From Ichi Orihara’s essay Gazing and Rembrandt’s Shadow, published by Hillside Gallery in 2017.]

“The skirt folds up, and the ‘whisper’ emerges.” This was the inspired phrasing of Xia Jifeng, my companion on this visit to Masaru Shichinohe, and it is just like Roland Barthes’ subtle definition of erotica,[See Roland Barthes (1915–1980), The Pleasure of the Text, Tu Youxiang, trans., Shanghai People’s Publishing House, 2009.] but erotica does not occupy the center of gravity of Shichinohe’s expression. In typical Japanese patriarchal erotica, the innocent girl is destined to completely open herself up, body and soul, under torment and humiliation, and admit she has been conquered by lust. Shichinohe’s erotica, on the other hand, holds its tongue: his girl has gone through puberty, or is in its early stages, but seems not to have latched onto the temptations of the outside world. She fixes the frame within a childhood atmosphere about to disappear, and in that unique moment in time, she seems to suddenly have the power to refuse to grow up.

Actually, the “whispers” breathe emotion and life into the dolls, and are a process of awakening the artist’s sense of self. The “whispers” are an antenna pointing at the mystery of life, keenly picking up information on time, death, pain, memory and emotion, while refusing to translate the riddles into answers, or perhaps there are no answers, only a series of confluences: images, atmospheres, structures and colors have a momentary sense of certainty. Clearly, the entry of the girl’s image has made for a thicker air of privacy. We feel like we are obvious voyeurs, just as when we enter into Shichinohe’s studio. According to Shichinohe, this girl, like the boy before him, is a facet of himself, or, compared to the sex dolls of patriarchal design, it is more neutral. Long ago in the psychoanalysis of Carl Jung, we learned that “animosity” and “anima” are two leanings that exist within all of us. Perhaps, in his painted world, Shichinohe is fortunate in having realized the dream of being both sexes.

Shichinohe’s language and techniques were first inspired by Vienna Fantastic Realism, and went on to absorb influence from Surrealism, Photorealism and even early Renaissance styles. He studied architecture in his youth, and the traces of architectural diagrams remain in his art today. In his paintings, we find a hybrid of restraint and mystery. At the moment of best expression, time and space come to an astonishing standstill, or, to paraphrase Erwin Panofsky, the person and pose are elevated to the level of pure existence.

-2014-布面油画-145.5×97cm-600x900.jpg)