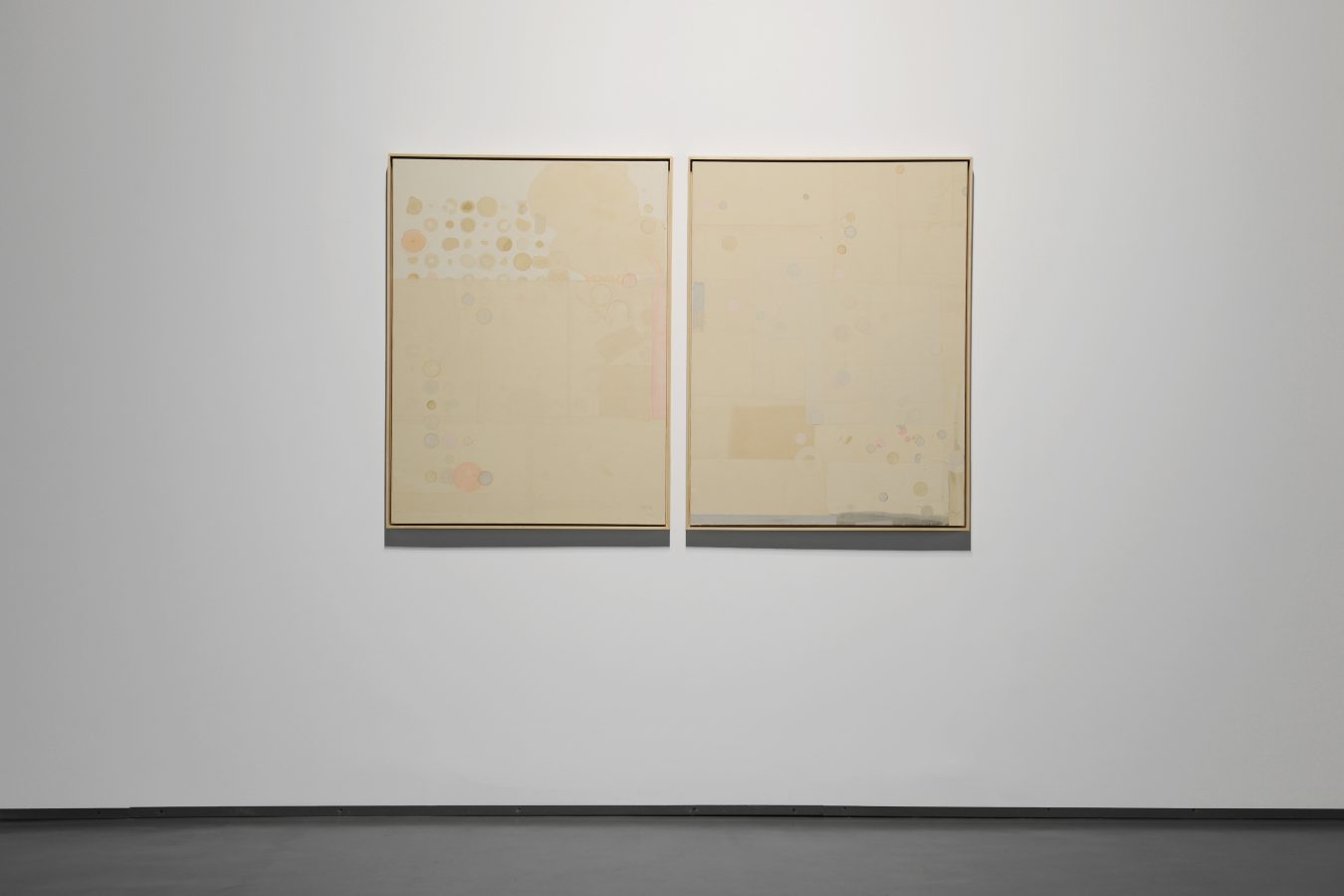

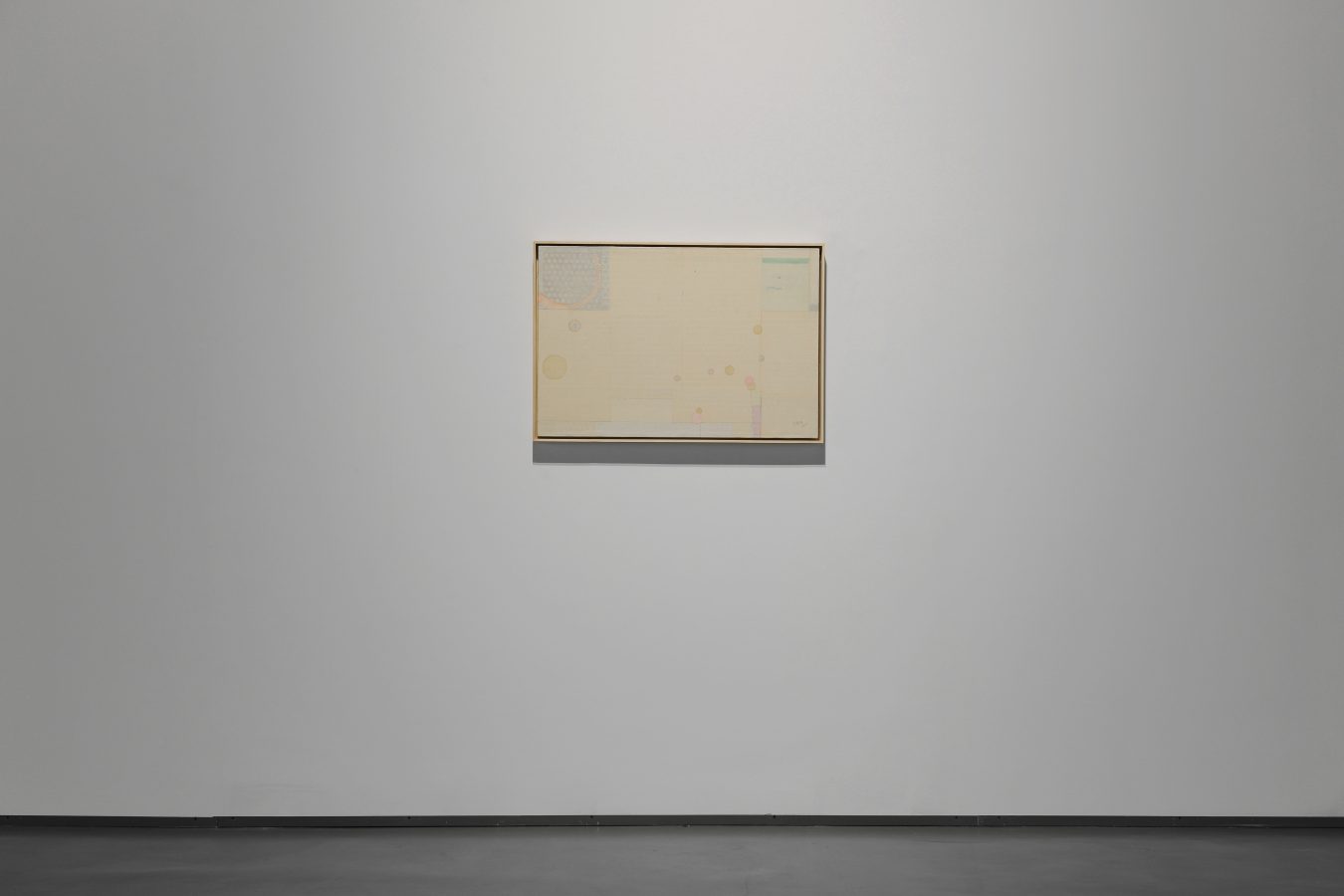

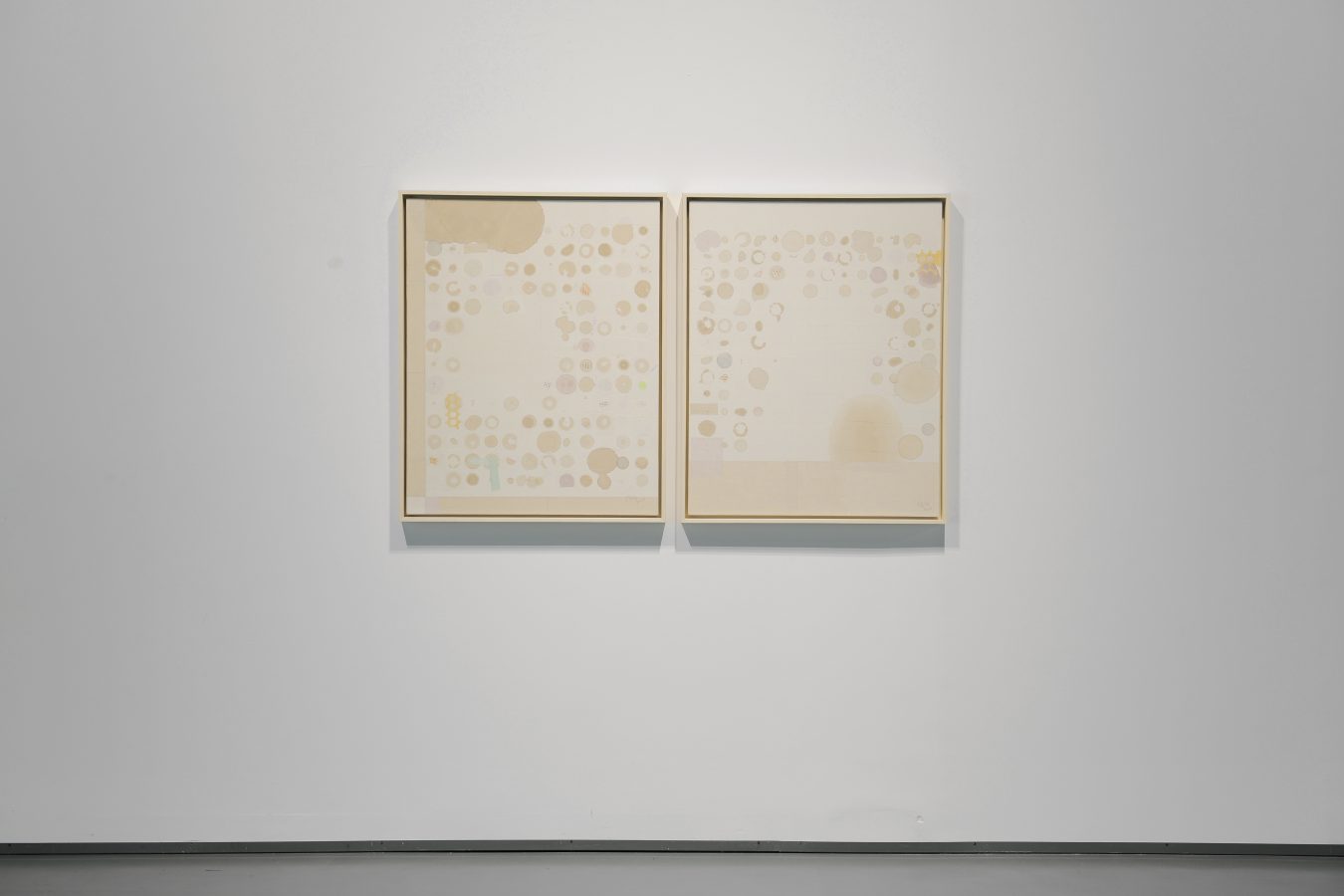

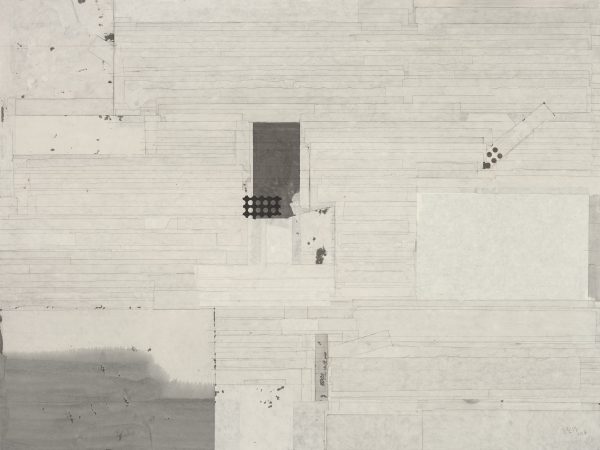

The Hive Centre for Contemporary Art has the greatest honor to announce that Perfection upon Finery: Liang Quan & Jin Shi will be inaugurated at 4.00 p.m. on the 8th of Nov., 2014. The exhibition is curated by Xia Jifeng and will last till the 8th of Dec., 2014.

The term Perfection upon Finery (originally meaning laying colors on the plain ground) stems from a discussion between Confucius and a disciple that took place some 2500 years ago. The original passage reads: “Zi Xia asked, what is the meaning of the passage, ‘the pretty dimples of her beautiful smile, the clear black and white of her eye, colors against the plain ground’? Confucius said, the business of laying the colors follows the preparation of the plain ground” (The Analects—Ba Yi). Zi Xia was likely asking Confucius for help in interpreting a poem on beauty from the Book of Songs. The founder of Confucianism used the rhetorical device known today as metaphor to provide a simple answer. Confucius had no intention of discussing the “business of painting,” but ever since, this phrase has served as a classic lesson in painting, as well as a koan for Chinese philosophy and aesthetics.

There have been many differing interpretations of Perfection upon Finery, which can mainly be summarized by the opposing views of Zheng Xuan from the late Han Dynasty and Zhu Xi of the Song dynasty. To approach the linguistic confusion over whether the business of painting precedes or follows the plain ground would drag us into an archaeological discussion of painting technique. On the surface, Confucius was using the rhetorical device of metaphor to discuss the principles of painting, but he was actually leading into the traditional philosophical and aesthetic views of Chinese tradition; “plainness” is the true core of the discussion. He advocated “enjoyment without licentiousness, grief without hurtful excess.” Maintaining moderation and genuineness has always been the standard for character among traditional intellectuals, as well as a unique aspect of Chinese cultural tradition.

This Confucian view of philosophy and aesthetics has undoubtedly influenced the aesthetic standards of Chinese traditional art. “Plainness,” has always been an endless pursuit in Chinese painting: a good artwork must contain a harmonious, pure, fresh and simple air, corresponding to the Confucian ideals of moderation, tranquility and introspection. The exquisite always returns to the prosaic, the artificial to the natural. When painting must be consumed a riot of shimmering colors before realizing the value of plainness and purity, does this lead us to yet another interpretation of Perfection upon Finery?

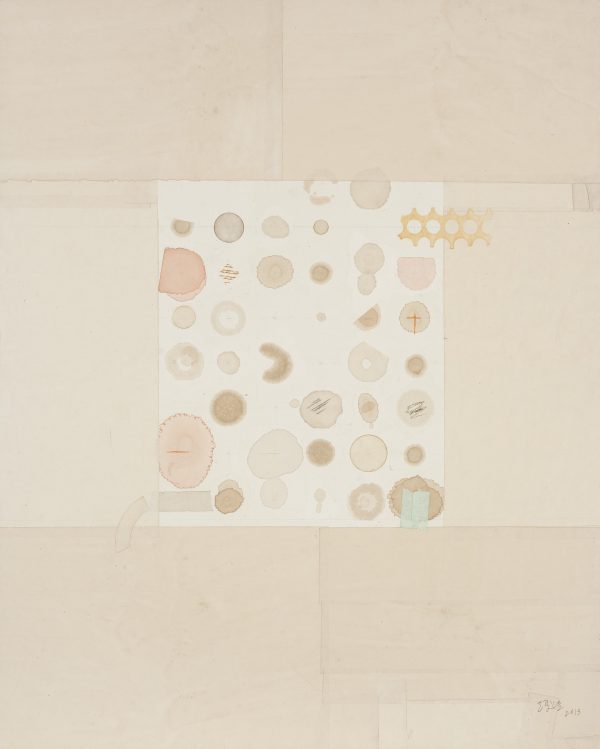

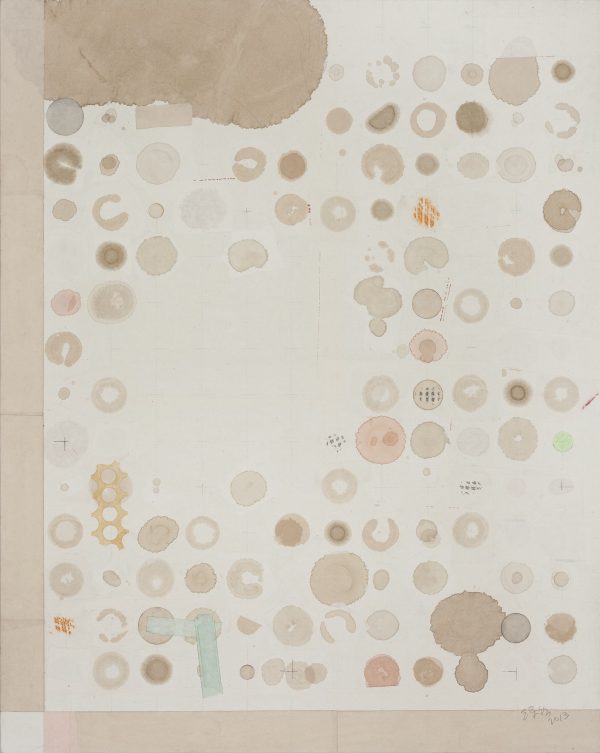

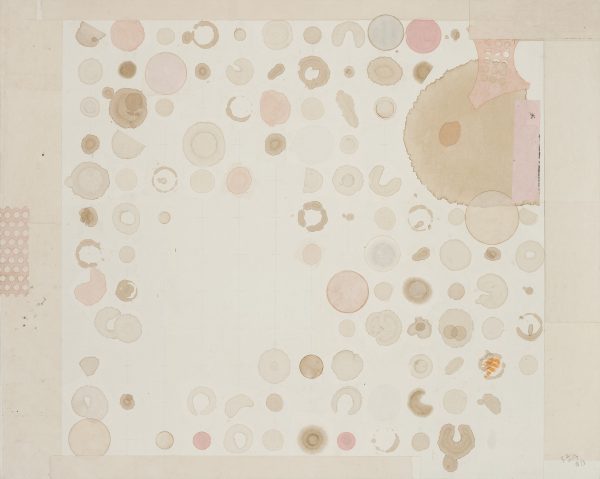

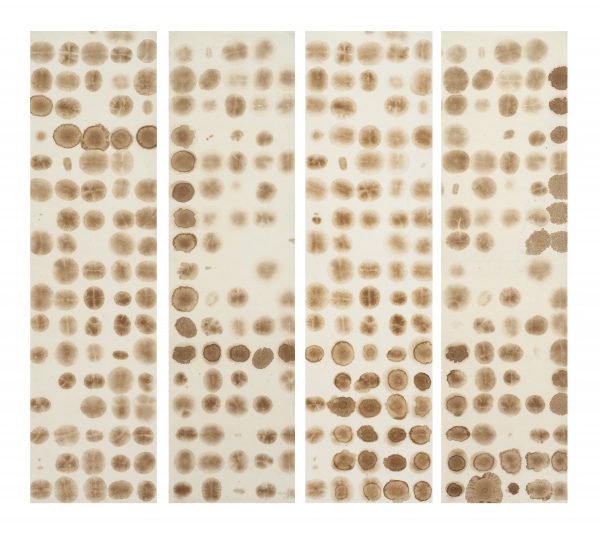

In this joint solo exhibition, artists Liang Quan and Jin Shi have both independently chosen tea-related themes. Just like the philosophical and aesthetic intentions conveyed in their work, the arts have met with an unplanned encounter with the Confucian view of Perfection upon Finery in the real world. Through the path of form, their works have maintained artistic contemporaneity, while also building an aesthetic channel of discrepancy and commonality to traditional aesthetics.