Hive Center for Contemporary Art is thrilled to announce Wang Xinyan’s upcoming solo exhibition “Night after Night” at our Shanghai space, on view from 28th June to 20th August 2024. This exhibition unfolds new creative development arising from Wang’s first solo exhibition at Hive’s Beijing space in 2023. Curated by Yang Jian, this is the artist’s first solo project presented in Shanghai.

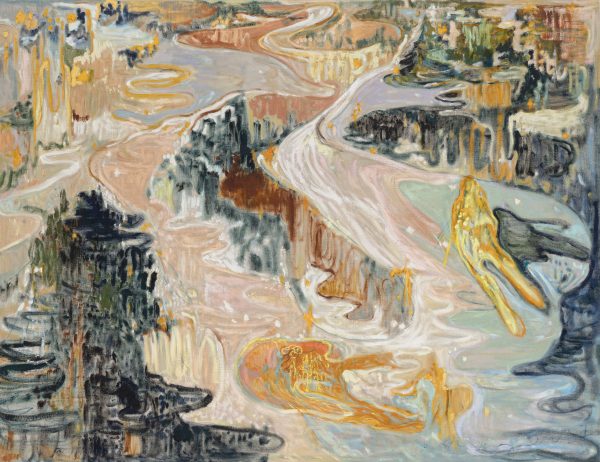

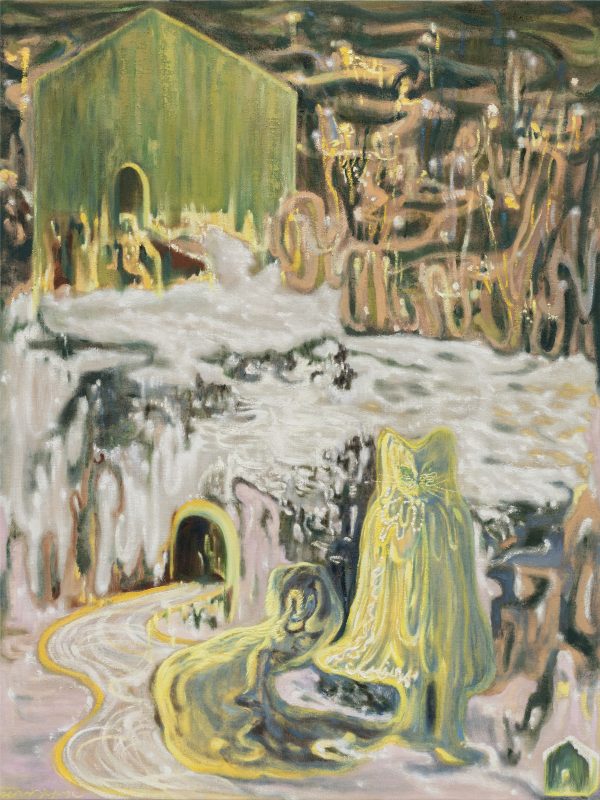

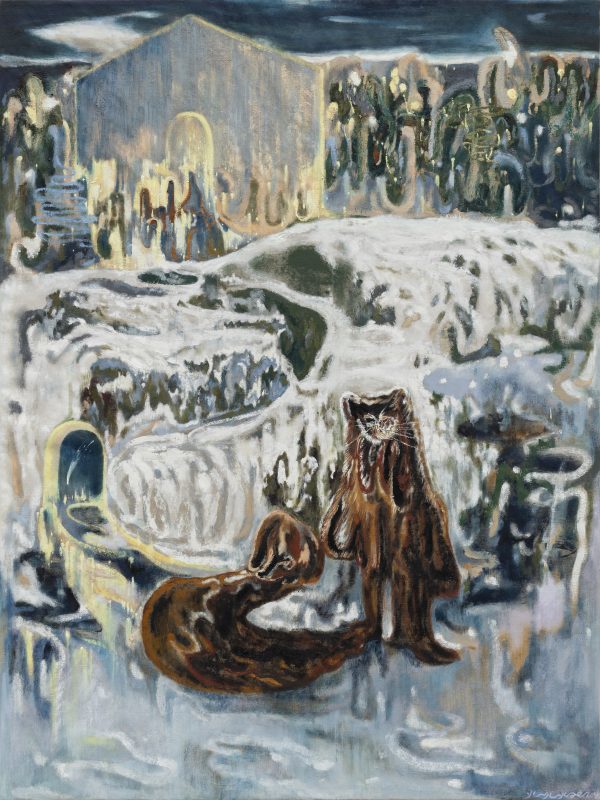

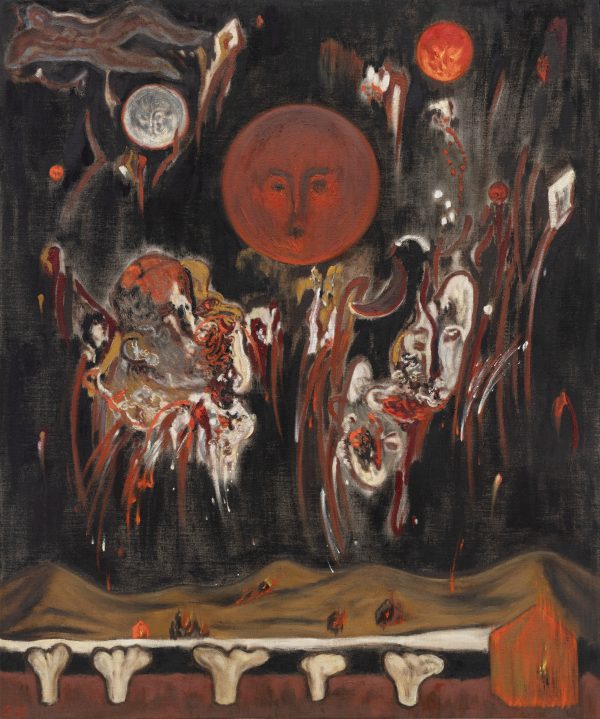

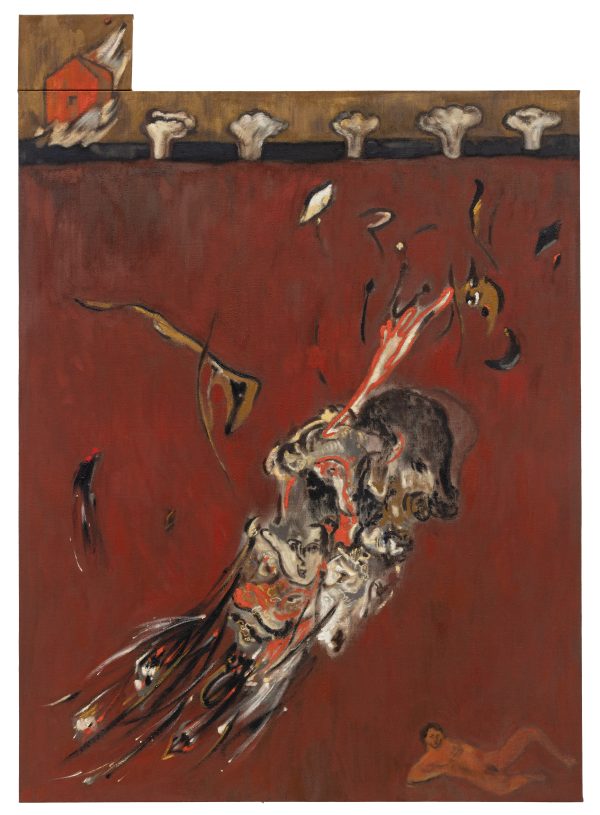

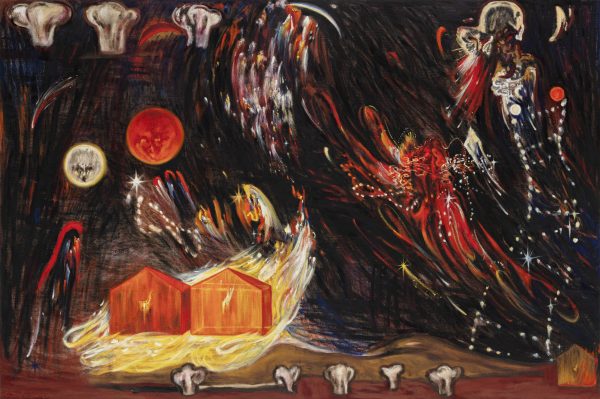

Following her experimental attempts, Wang Xinyan has gradually arrived at a time and space of darkness, where the social reality is suspended. In an environment where external light becomes absent night after night, the conflicts and confrontations between the ice and fire, perceptible even to the eye, ensue. Through personal fabrication and fantasies of luminous matter in the darkness of conflict, the artist has constructed a very personal approach to expanding her perception towards the outside world, or rather, the vision of an image and the visual and tactile sensations of our viewing have become the extensions of each other. We cannot consider the artist’s fabrication of this frozen, dark world as a futile attempt at refusing to face the disappointment or escapism that pervades this society. Rather, inspired by the idea of psychoanalysis, the artist transforms fairy tales, dreams, memories, and the anthropomorphised self-portrait into an ostensible visual space that intends to penetrate both life and the present, attempts to reveal more profound existential perspectives through her work, and explores the subconscious frenzy of humanity, the hallucinations guided by intuition, and the irrational energy of the mind.

“I prefer people whose character resembles a frozen lake to those who are more like marshes. The former are cold and hard on the surface, yet deep, roiling and alive underneath, whereas the latter seem soft, spongy, but inert and impermeable at the core.” — Excerpt From Sylvain Tesson’s The Consolations of the Forest.

Whether in her native Beijing or in Chicago where she lives and studies, Wang Xinyan always discusses her experience of working and thinking alone in the coldness – perhaps the sense of detachment from the external world that comes with the coldness is more fitting for Wang, who prefers to work and reflect in solitude. The artist has therefore emphasised a spectacle space and time, enchanted by snow and ice and enveloped by the shadow of night, and has created many intriguing figures: a cat-faced yeti, a Christmas tree with an old man’s face, an ice skater without a face, a cabin that is always on fire, and the sun that rises at night. These strange figures, whose identity the artist cannot fully explain, are perhaps the result of her perceptual development and intuitive accumulation, and have slowly crept into and inhabited the depths of her memories and consciousness; they are elusive and indiscernible precisely because they are not arbitrary existences in the physical world, or that they have been rearranged in their own sense. They cannot be simply generalised as a psychological context or a spiritual totem, but rather, as a proto-formation of desire that combines the artist’s vital and creative impulses, the true origin of the modal logic of these figures. It seems to me that this also encompasses, in some psychological way, the complex social psychology that Kafka articulated in Metamorphosis, where people often want to become a beetle, an oddity, dissected from society, family, and even humanity – they want to become transparent from time to time, but also in the spotlight, and ultimately, abandoned.

After establishing a foundation of creative skills from the affiliated high school to the graduate school of the Central Academy of Fine Arts in China (CAFA), Wang Xinyan’s life and study in Chicago gradually led her to comprehend painting as interpreting and expressing her perception. The emphasis on the ability of representation in institutional Chinese education colliding with the modernist concept of the West has deepened Wang’s understanding of the complexity of painting as a reality, which includes not only the knowledge and exploration of the medium itself, but also the consideration of the painted subject’s materiality, and more importantly, the transcendence that may be encapsulated. It is, in short, how to perceive and understand the reality in which we exist. Meanwhile, in a context of diverse educational backgrounds, art historical structure, and various cultural perspectives, Wang aims to transcend the linearity logic of the history of painting and the disconnection between the East and the West, and searches for some common ground between concepts of different eras. Painting, as a consciousness, can elude the constraints of figure and form on painting, and thus escape the metaphysical constraints, where superficial discussions of the meaning of figure come to a rest.

Here, we seem to slowly notice that painting for Wang Xinyan has become a way of acquiring originality, where the gradual growth of consciousness follows along with progression, constantly marching forward, mobilising a sharper and more delicate perception after the necessary accumulation of habitual pace and effort. Thus, the artist’s fabricated dimension of images becomes a staged illusion, which she has created for herself in advance and then waited like a caretaker for the figure to evolve from the image until it is shaped in the process of painting – this figure is no longer a reality witnessed by the eye, nor is it historical. The illusory lens, with lights and emphasised landscape, extends and interposes the space, and the figures that embody the artist’s understanding of painting and profound perception keep on emerging, in movement, ablaze, and illuminating the endless night in this dimension.