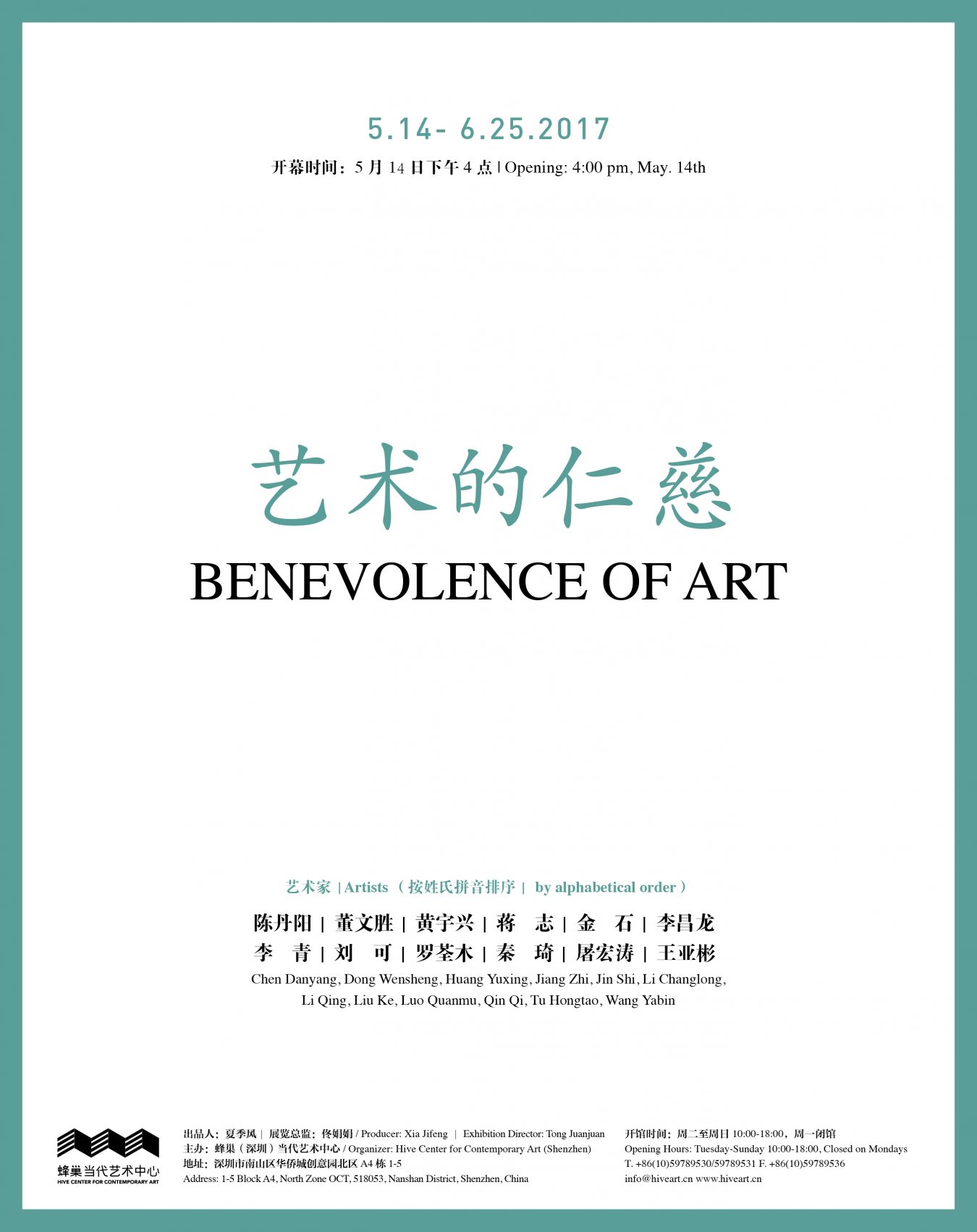

Hive Center for Contemporary Art (Shen Zhen) is pleased to announce its second round of exhibition “Benevolence of Art”, the exhibition invites 12 artists to participate: Chen Danyang, Dong Wensheng, Huang Yuxing, Jiang Zhi, Jin Shi, Li Changlong, Li Qing, Liu Ke, Luo Quanmu, Qin Qi, Tu Hongtao and Wang Yabin. Inaugurated 14th May.2017, the exhibition will be on show at Hive’s Shenzhen space (OCT Shenzhen) until 25th Jun. 2017.

American Russian writer Vladimirovich Nabokov, when mentioning his fiction Lolita that he was proud of in an interview, thought of the astounding expression in the work as a way that should be taken for granted by a qualified writer to manifest artistic will and freedom, and he also held that his creation aimed to provide an aesthetic bliss and to explore art and aesthetics, had nothing to do with morals and ethics. Regarding the definition of “aesthetic bliss”, he pointed out that it was “a sense of being somehow, somewhere, connected with other states of being where art (curiosity, tenderness, kindness, ecstasy) is the norm”. The word “art” is followed by “curiosity, tenderness, kindness, ecstasy” specially highlighted in the brackets. Similar expression can be found from the remarks of Roland Barthes, a French semiotician. In his speech “I’ve Been up Early for a Long Time”, he thought that the motive for creating fictions stemmed from a feeling “somewhat related to love”, which should be “benevolence, generosity, tolerance and compassion” if required a name. What Barthes asked for was a theory that aroused compassion in the fictions. However, when compassion has caught us in the “true moments” of fictions—as he put it, it has completely nothing to do with the realistic environment and couldn’t be found in any fiction theories including his own spectacular ones.

Does Nabokov and Barthes’ coincident view, that is, the so called “benevolence and compassion” or feeling “somewhat related to love”, also exist in art? The answer should be affirmative. Except for the difference in the forms of the works, literature and art have always coincided with each other. Just as a writer uses ancient words, any brilliant artist’s creation itself actually explores the truth of languages’ clichés, that is, the creation procedures and materials of art itself—scarcely anything has changed in this level ever since art became art and an action for human to express emotions and spiritual longings. It’s just as the words used by writers are available for everyone; also as the creation methods and materials of painting nowadays hardly differ from those drawn on by the artists one thousand years ago.

However, besides the component materials, the most fascinating charm of art may lie in “the feeling”, that is, the benevolence that art itself possesses and conveys to audience, precisely brought about by what is beyond the materials themselves. The real reason for Joseph Mallord William Turner crying in face of Claude Lorrain’s painting “Seaport at Sunset” is never known to us. He was said to be upset that his creation could never excel that of Lorrain, whose techniques now appear less superb and touching than his. Neither can it be understood by us how the audience feel as if they had entered a worldly church and had been at the mercy of a divine power and thus experienced complicated emotions of meditation and confession when they entered Rothko Chapel in Houston, USA, enveloped by Mark Rothko’s large paintings of simple colors and dull tones. Maybe the historian Robert Rosenblum is right in saying, the Western tradition of religious art seems to have finally lost its complexity of narration and all physical images at this moment, leaving to us infinite darkness, compelling existence and a choice to make between having everything and nothing.

It is somewhat ridiculous to interpret the meanings of art from a moral or ethical angle. However, just imagine the outcome of an artist or audience being numb to the “horrible temptation of benevolence” (quoted from Brecht, a German dramatist and poet). Artists fail to feel tempted by benevolence during art-making, means that neither can the completed artworks reveal benevolence nor can the audience feel benevolence of art. Thus, art may not be art any more but an object or excuse that exists in its name. Of course, benevolence is not the only virtue of art, at least not the greatest one that it should possess. As the British scholar Michael Wood said, if an artist has to select a virtue for art during creation, honesty is a good choice obviously.

The advent of the information age has unprecedentedly facilitated communication among people and the voice and video technology enabled people thousands of miles away to get in touch. However, the distance between the audience and art has not been shortened but lengthened instead. The audience’s feeling and experience is of more and more poverty in face of art. American scholar James Elkins held in his book Pictures & Tears that the overemphasis on rational cognition could be regarded as an unforgivable bad habit, either in the field of research on art history or in the art education for the public. We haste to swallow plenty of knowledge about art, busy ourselves in identifying each famous painting and anxiously learn to distinguish art schools and styles, but forget the real intimate relationship between painting and human, that is, touch and tears—benevolence brought by art.

In fact, to recognize anew the benevolence of art and feel the feeling “somewhat related to love” is to restore one’s ability to appreciate art and one’s spirituality, and also seems to be a noteworthy academic orientation in the realm of contemporary art. It’s not only for painting, but also for the existing and newly developed types of art; not only for artists, but also for audience, art lovers and professional collectors.