Hive Center for Contemporary Art will present ten artists of diverse backgrounds at Art Basel Hong Kong 2021. These ten artists, spanning from the 60s to 90s generation, have been profoundly involved in different areas of painting. These artists include Liu Gang (b.1965), Duan Jianwei (b.1969), Bu Di (b.1970), Wang He (b.1983), Leng Guangmin (b.1986), Qian Jiahua (b.1987), Gong Chenyu (b.1988), Ji Xin (b.1988), Pu Yingwei (1989), and Zhang Ji (b.1993).

The creative aspects of these ten artists are merely anchored within the offering of specific information by the outside world. More importantly, their creations internalise their emotions as the weavings of their worlds—this is especially accurate for painters. For years, their disciplined manners seem like a far cry from the irresistible trends in the age of video, but in fact, the pursuit of permanence is an eternal theme. Particularly in the present, as we urgently seek the comfort of imagery, within the past ten years, the torrent of contemporary media has presented us with uncontrollable fragments. In contrast, temporary interception or selection of such fragments cannot ease our minds. We re-engage with the discussion of painting, including but not limited to the expression of aesthetics, in such a peculiar moment in history. Attempting to connect with various historical moments as well, we aim to confirm the identity of painting in the present.

Bu Di. 2019 5-6. 2019. Acrylic on canvas. 180×150cm.

Bu Di was born in Beijing in 1970. His paintings broadly draw on the figuration methods of Chinese and international art history spanning across the timeline; they suggest a sense of contradiction and mystery. His work visually references modern aesthetics—Buddhist art, early 20th-century Western Avant-Garde sculptures and paintings, traditional Chinese calligraphy, and even Neorealistic films. Bu Di’s work is not bare schematic extractions of the imagery he profoundly appreciates; he constantly derives within the same work. His process of simplifying elements resembles our observation of Picasso’s abstraction of the ox or Mondrian’s tireless overlapping of the tree while moving towards abstraction. Distinct from his predecessors, Bu Di’s formal refinement results from his continuous creation and accumulation. His creative process is not merely a path of compressed reflection within the frame. In this process, he deliberately reveals some information that can also be recognized as the mountains and the rocks in traditional Chinese Mountain and Water paintings—this is his adherence to Modernism. Instead of whether to emerge from a visually abstract presentation, the more important thing is the principles. Eventually, in the painting, the contours and shadows of Brancusi’s sculptural figures are positioned on the left, the pine cone scales and rocks are on the right side. At the bottom, the still-frame processed with cinematic language is blended with the artist’s thinking on the linguistics of multiple forms. Besides, the practice of the near, middle, and distant view of the painting unfolds Bu Di’s subtle understanding of the concept of space in traditional Eastern paintings.

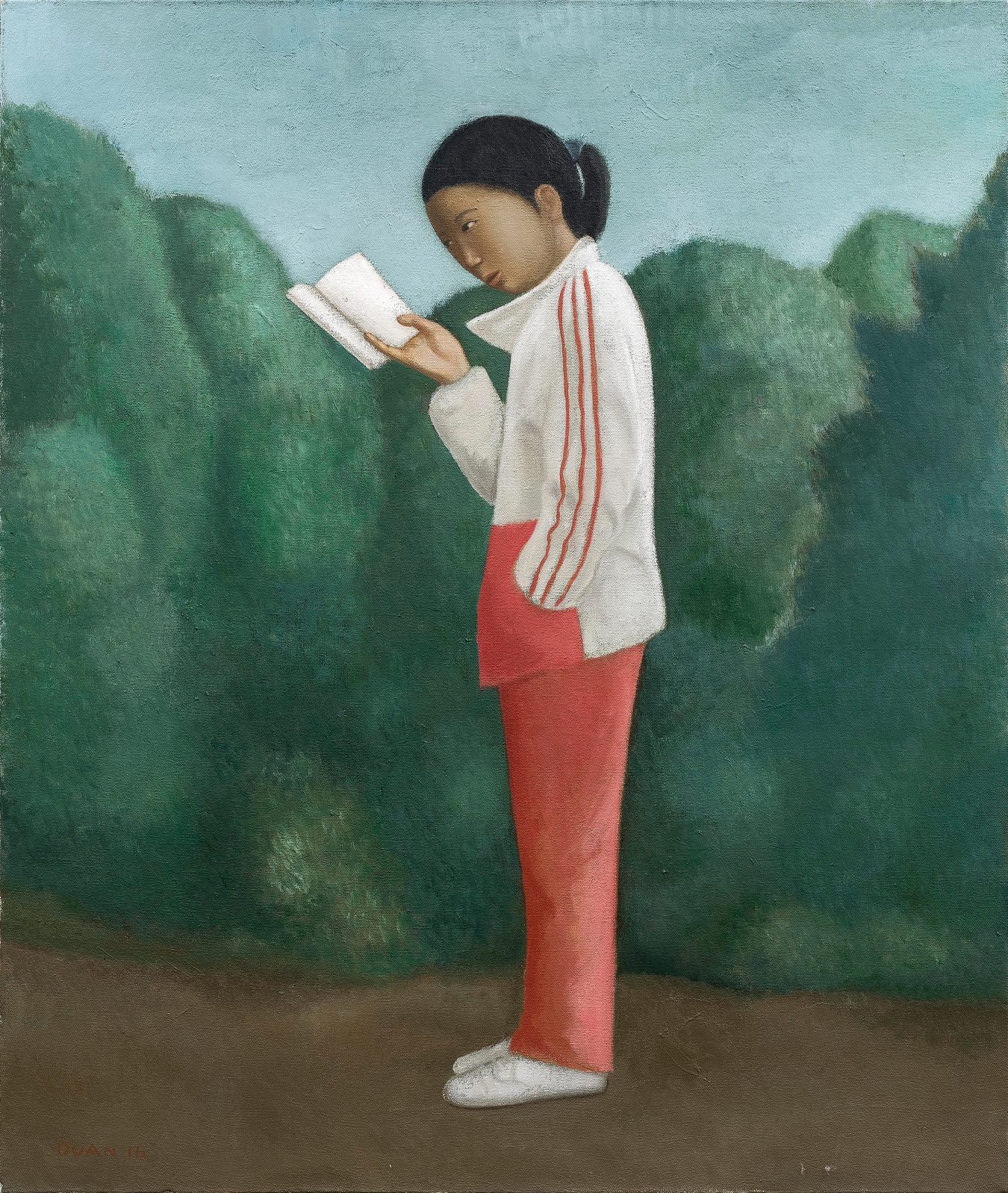

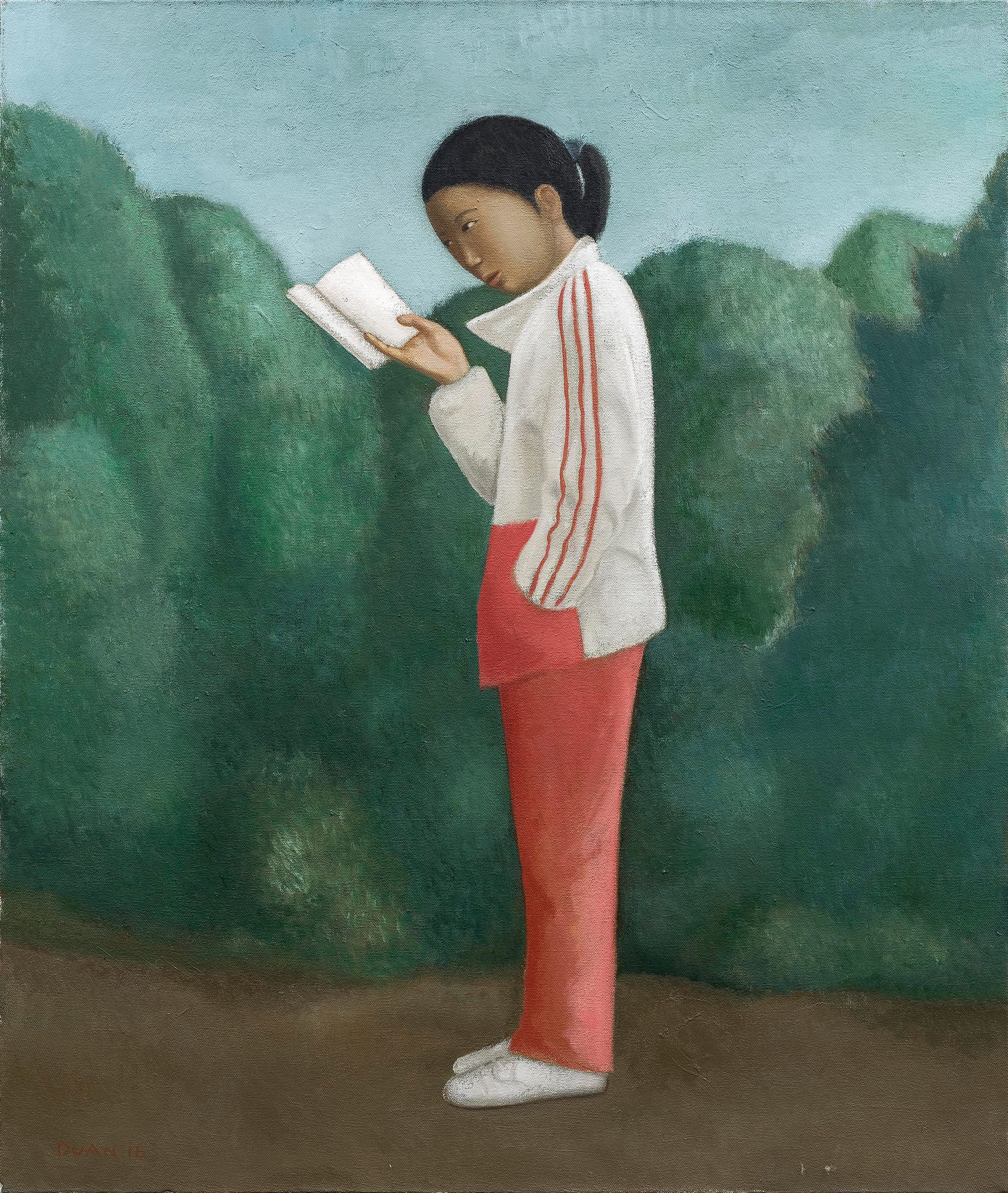

Duan Jianwei. Read. 2016. Oil on canvas. 130×110cm.

Duan Jianwei was born in 1961 in Xuchang, Henan Province. He graduated from the Department of Fine Arts of Henan University and now teaches at the School of Fine Arts of Capital Normal University. Portraits have been a consistent theme for Duan Jianwei. From the very beginning of his career as an artist, he deliberately adopted the subject of rural life from the Central Plains as the dominant theme of his paintings. In this cultural context, human beings, like everything else, are, in a sense, the fruits of the land. And the subjects in his paintings are not only individuals but also the vehicles of a particular idealised social spirit. To this extent, through his depiction of rural life and peasant figures over the past thirty years, Duan Jianwei has discerningly portrayed Chinese ethnicity’s internal essence and aesthetic characteristics while addressing the subtle interrelationship between humans, the Earth, and everything else in a precise artistic language.

The figures in Duan’s works invariably possess the physical characteristics of the Central Plains people. Oval and smooth facial contours, tanned skin, and long, narrow eyes almost summarise the facial features of the numerous subjects Duan has painted over the past decades; this is followed by Duan’s continuous research of the figuration methods employed in the early Renaissance. When perspective had not yet been developed, when perfectly proportioned bodies had not yet replaced flatter figures, a significant number of works from the late Medieval and early Renaissance reveal a more uncanny and ethereal atmosphere. Similarly, the sculptures of the Northern Wei dynasty were profoundly admired for their aesthetic influence, which could be traced back to the Western Regions and even to Greece. The products of hybridised cultures always manifest an extraordinarily natural and pristine vitality. His study of the stylistic approaches to religious painting furnishes Duan Jianwei’s works with an enduring sense of time. The duality of time is concealed in classical paintings coincides with Duan’s observations and perceptions in reality. When presented onto the mortals in his world of painting, it collides with the dual qualities of the transient and the permanent, the secular and the sacred, the ordinary and the exceptional.

Gong Chenyu. Idol-Diver. 2021. Oil on canvas. 150×100cm.

Born in 1988 in Qiqihar, Heilongjiang, Gong Chenyu graduated from the Sculpture Department of China Academy of Art in 2012 with a Bachelor’s degree and the Oil Painting Department of China Academy of Art in 2015 with a Master’s. Being created in different power contexts, Gong Chenyu’s works perpetually focus on idols, whether human or sacred. His work is not a recreation of representation for the gods but extraction of transformation from texts or other images, not in the sense of natural forms, but by resorting to the painting itself. According to Gong Chenyu, humans needs to pursue an agitation that transcends nature. Consequently, Gong Chenyu’s work follows the MacGuffin, a Hitchcock film technique. In other words, his subjects are not physically present beings or something that are not associated with reality but are the core of the conversation and even the whole narrative. The “idol” is not real but remains in a constructed form; they are a psychological need or idea of human consciousness at a specific stage. This is also why the imagery and textual references in Gong Chenyu’s works cannot always be traced. Gong Chenyu seeks a kind of cognitive dislocation and a distinct blurring of details. Almost similar to a cluster of fog, he can only recognise hints but cannot uncover them. This barrier created by his painting also constantly urges the viewer to shift their minds to a broader elsewhere. Bondage and captivity are common themes in Gong Chenyu’s works, and Idol-Diver emphasises the sense of suffocation and the power dynamic between the characters.

Ji Xin. White Cat. 2021. Oil on canvas. 190×150cm.

Born in Nantong, Jiangsu in 1988, Ji Xin received a bachelor’s degree and a master’s degree from the Oil Painting Department of China Academy of Art in 2010 and 2013. Ji Xin’s work derives from the classical. Formal expressions in the works of Western masters and the introverted sentiments in traditional Eastern paintings are the two essences for understanding Ji Xin’s works. In his creative process, Ji Xin reflects on the masters’ works from time to time. In his constantly developed perception, the artist hopes that history could nourish his art as much as the world of imagery that’s occurring at present. The artist anticipates for his work to be static while dynamic. Thus he has preferred elements that have maintained a genuine sense of distance from the current era in his work.

In White Cat, the artist places the female figure with the style of the Republic of China in the same space as the white cat and the antique TV set. For the artist, the female figure of the ROC is synonymous with romantic, liberal, bright, and beautiful; and what cats represent nowadays is a culture of healing. They may be imagery from different times and spaces, though the artist mingles these elements harmoniously. The contemporary internet culture has transformed everything into flattened existence; the same observation applies when viewing Ji Xin’s work. They are flattened, screened, and integrated with different kinds of cultural imagery. There is a literary significance in Ji Xin’s work. The implicit thread of the narrative hidden behind is the artist’s consistent cultivation of the dialogical structure among his artworks.

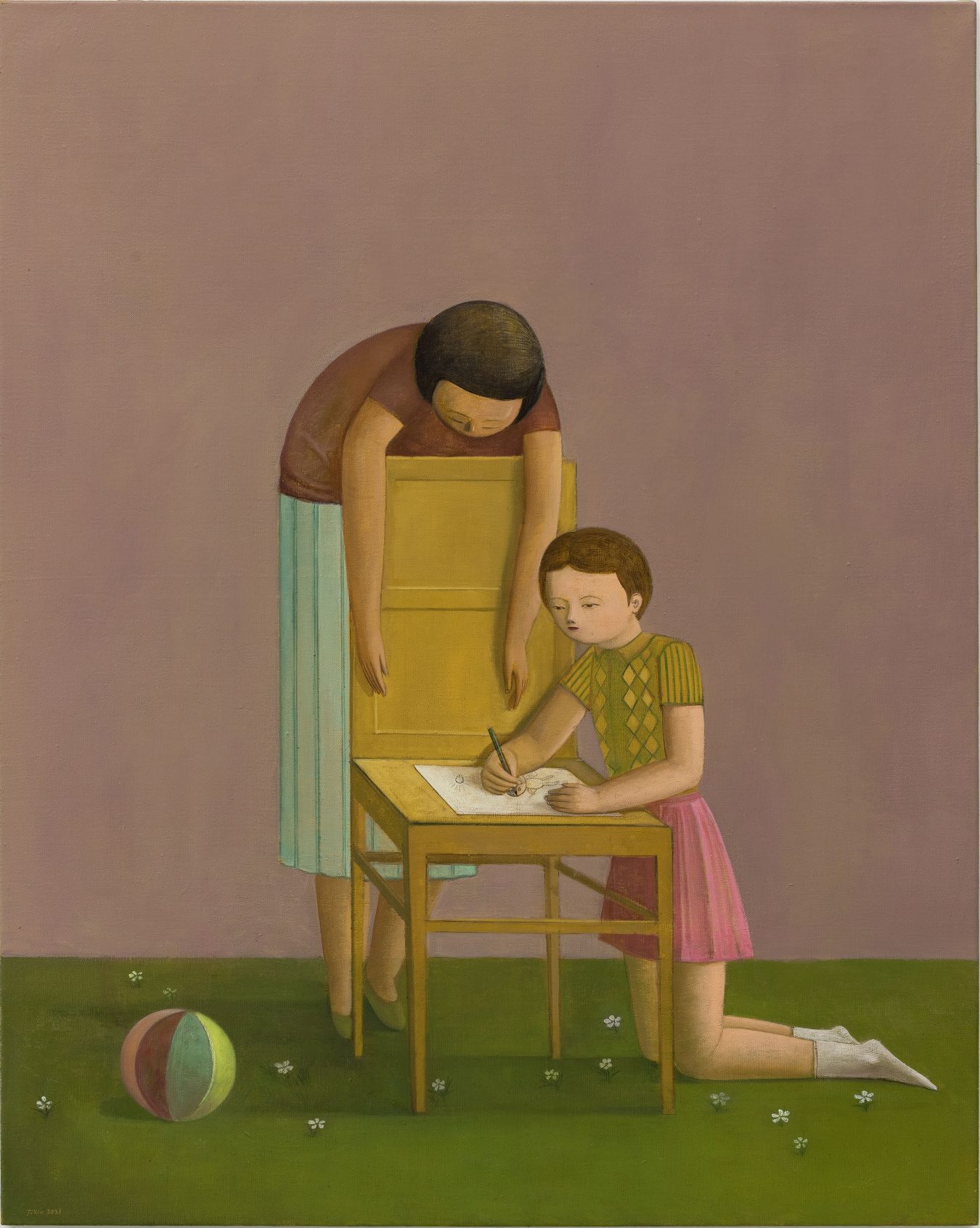

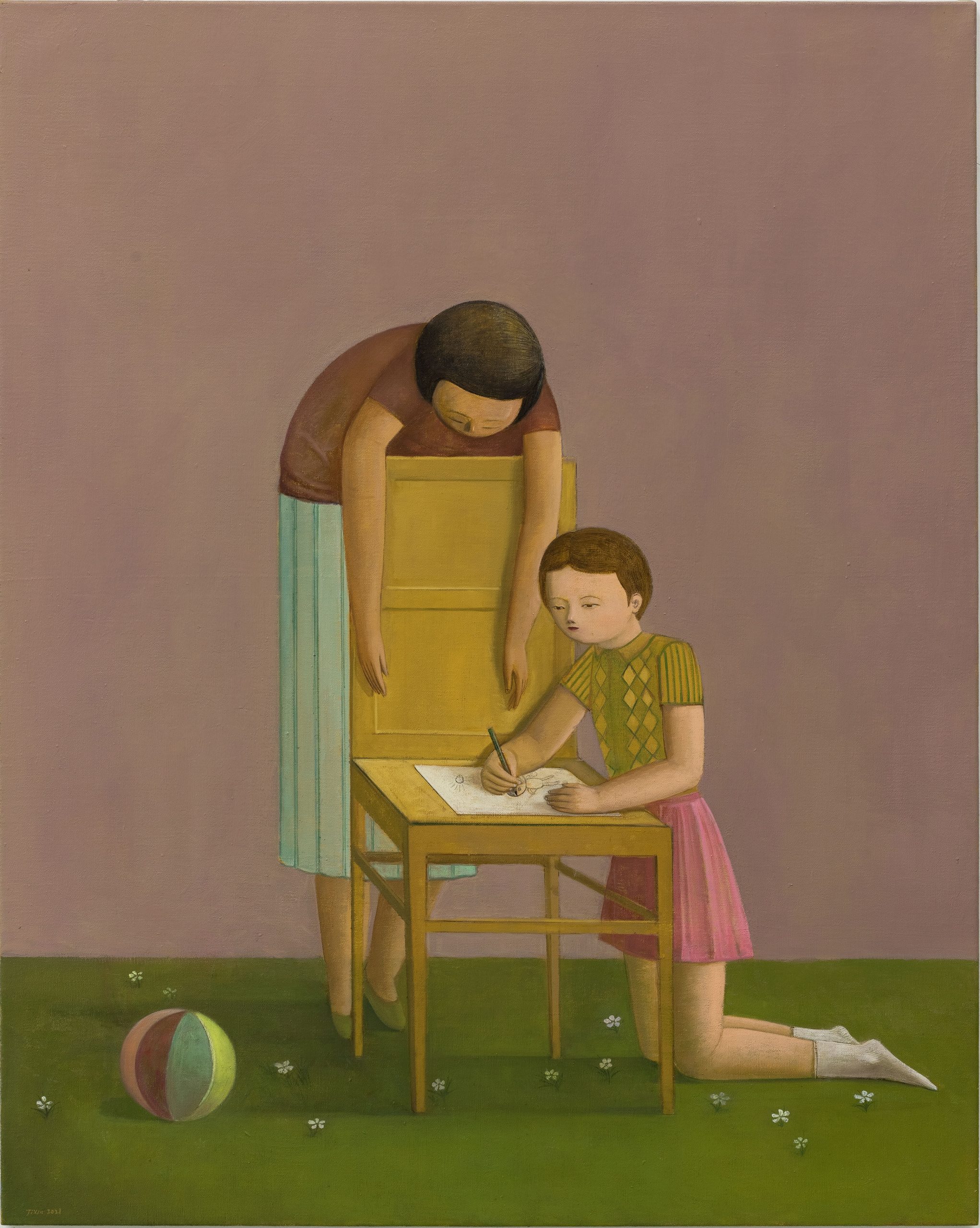

Ji Xin. Drawing Class. 2021. Oil on canvas. 120×150cm.

In Drawing Class, the artist has arranged the scene in a simplistic outdoor environment, with the background in muted and subdued pink. A sense of closeness is implied in the relationship between the background and the figures through the colours of the mother’s clothing, her head slightly bending down, and her arms stretched out. It also reveals the dedication of a mother figure. Correspondingly, the green grass and the girl’s clothing colours contradicts. The mother’s pale green dress and the child’s bright pink dress suggest an interactive and intimate relationship between the two. Ji Xin’s work aims to emphasise the glamour of East Asian women at various stages of their lives. Consequently, Ji Xin succeeds in supplementing the religious rituals of his previous works complemented by a realistic ambience. And in the process of retreating from the rituals, he captures a breath of tranquillity that is subservient to everyday life.

Leng Guangmin. Two Faces of the King. 2021. Mixed media on canvas. 200×150cm.

Leng Guangmin was born in Qingzhou, Shandong, in 1986. He received his Bachelor’s and Master’s degree from the Oil Painting Department of Tianjin Academy of Fine Arts in 2009 and 2012. He specialises in abstract painting and is a significant figure among the youngest generation of contemporary Chinese artists.

As one of the leading painters born in the 80s, Leng Guangmin, while studying at the Oil Painting Department of Tianjin Academy of Fine Arts, has already consciously explored a particular method to be liberated from the traditional patterns of painting. In contrast to the brushstrokes piled up with paint, Leng created a unique and peculiar painting language and logical paradigm. In comparison to Fontana’s direct cutting into the canvas to divulge the essence of painting, which could be regarded as visual confusion, Leng executes a structuralist composition on the base of the canvas, accumulating thick layers of cardboard with conflicting colours that are often complementary to each other. This process is still within the logic of painting, one that involves the use of traditional tools such as brushes. Once this process is complete, the real pictorial game of Leng Guangmin is just about to take place: the sharp carving knife slits the surface layer by layer to expose the underlying coatings of colour, exterior, and interior paintings resemble skin and flesh. In the means of carving, certain scraps of paper are perceptively left behind as a testimony to the artist’s violent manner of ripping the cardboard. Notably, the artist’s methods are repeated several times in the artist’s mind before this game begins, and it is only when the logic of the reason is consistent and whole that the artist truly begins to create. In a long path of time, the artist demonstrates how different types of subject matters react to his hands. After conquering time and again the ordinary images, such as furniture, plants, tableware, and other classical subjects of painting, Two Faces of the King hints at the artist’s return to the classic origin of painting, which is his treatment of the facial features of a figure. For Leng Guangmin, painting is a unique approach and a prolonged journey of self-conquest to distil a particular internal structure beneath the diversity of objects, which is an exceedingly abstract state of flux that can only be manifested through imagery.

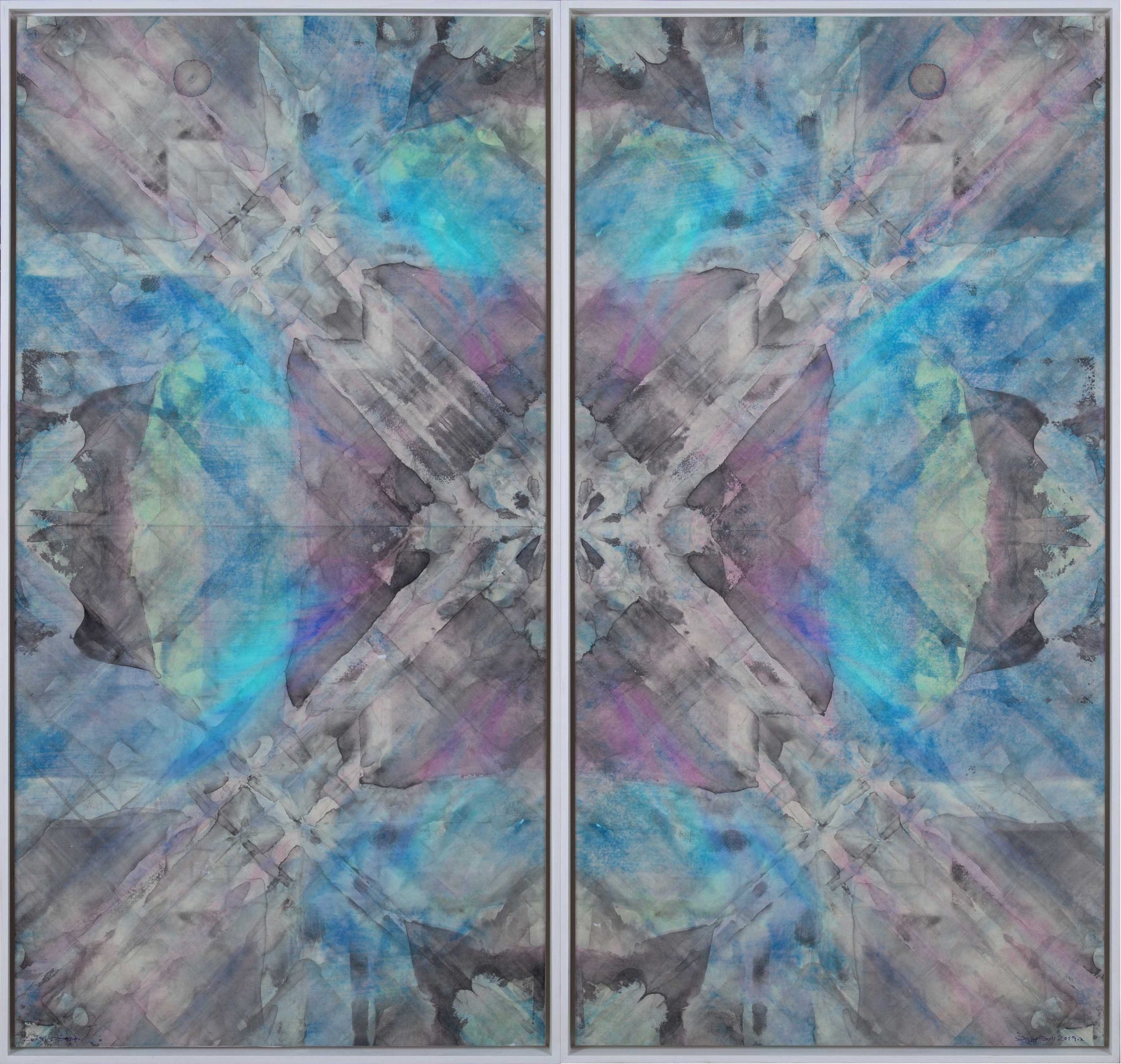

Liu Gang. 401209102. 2019. Mixed media on paper. 145×138cm×2.

Liu Gang combines the reversed date with codes as a naming method for his work, revealing rather indifferent rationality. His laminated works are based on Xuan paper, which traces back to the artist’s hometown, Anhui, a dominant producer for Xuan paper. In Liu Gang’s creative process, he initially blends water-based and oil-based paint on paper and then builds the main structure of the painting with rollers. Notably, after his work on paper is completed, the artist consciously employs stainless steel frame and anti-reflective acrylic that is rarely available in China, as well as a layer of inkjet colour on the back of the acrylic that mirrors the structure of the work on paper, thus creating two layers with the colours on paper. For Liu Gang, the research and practice of the latest materials are complemented by his in-depth examination and refinement of paper-based materials.

In terms of the content of the imagery, the artist’s application of the symbols ‘tick’ and ‘cross’ is originally a response to the traditional education system. Still, the air we breathe is under such a dome; this results from the visual deconstruction of our world. All visual forms and matters serve a world the artist is attempting to establish, a world that consists of individual and collective memory laminations, including all visual instants that are rapidly appearing, and the ever-compressed space for human survival in the process of industrialisation. In this world constantly being devoured by the so-called industrial civilisation, we have created an oppressing contemporary life contrary to primitive naturalism—new caves are arranged in a specific order one after another, forming a social spectacle pursued relentlessly and are complaint to consumption and desire.

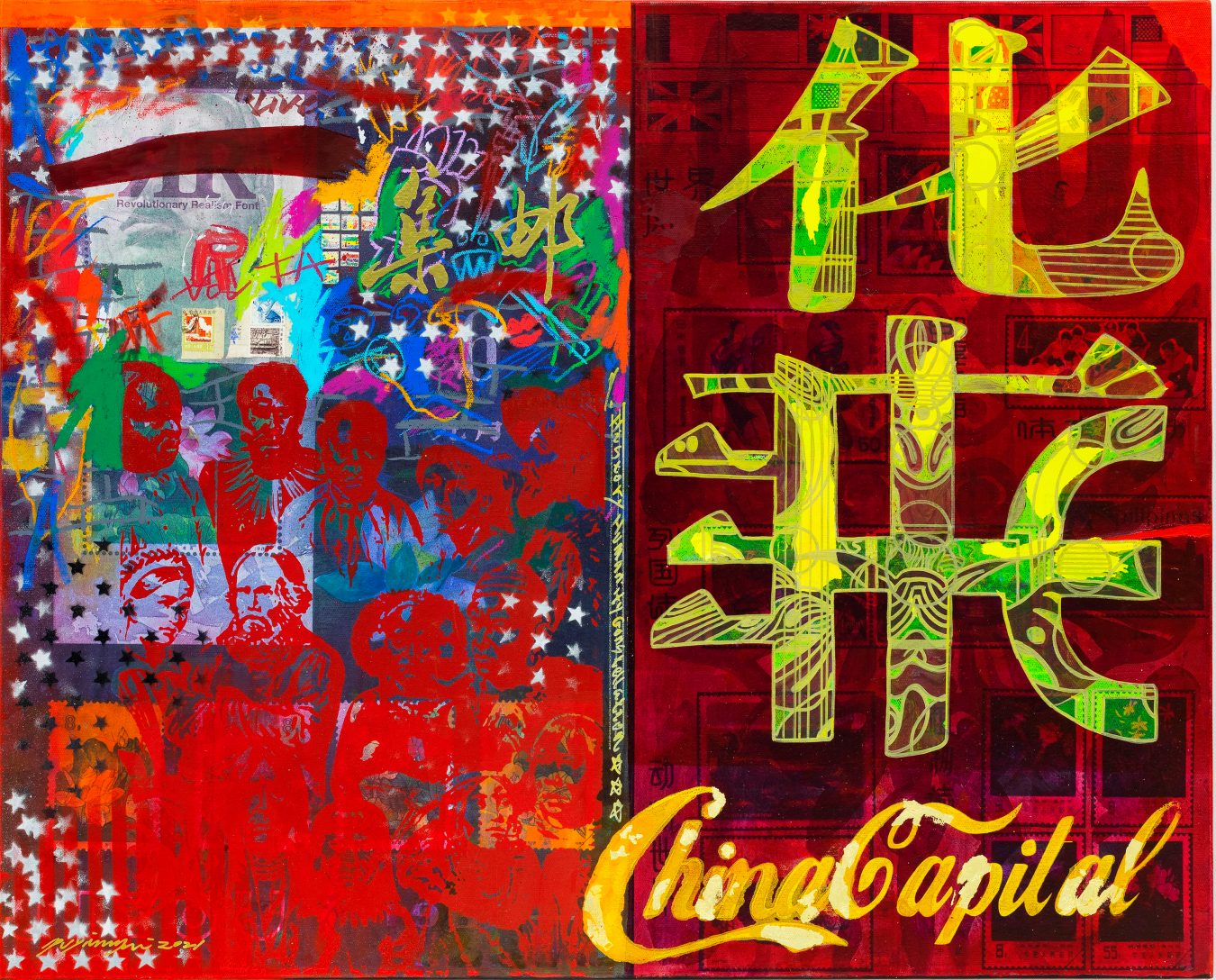

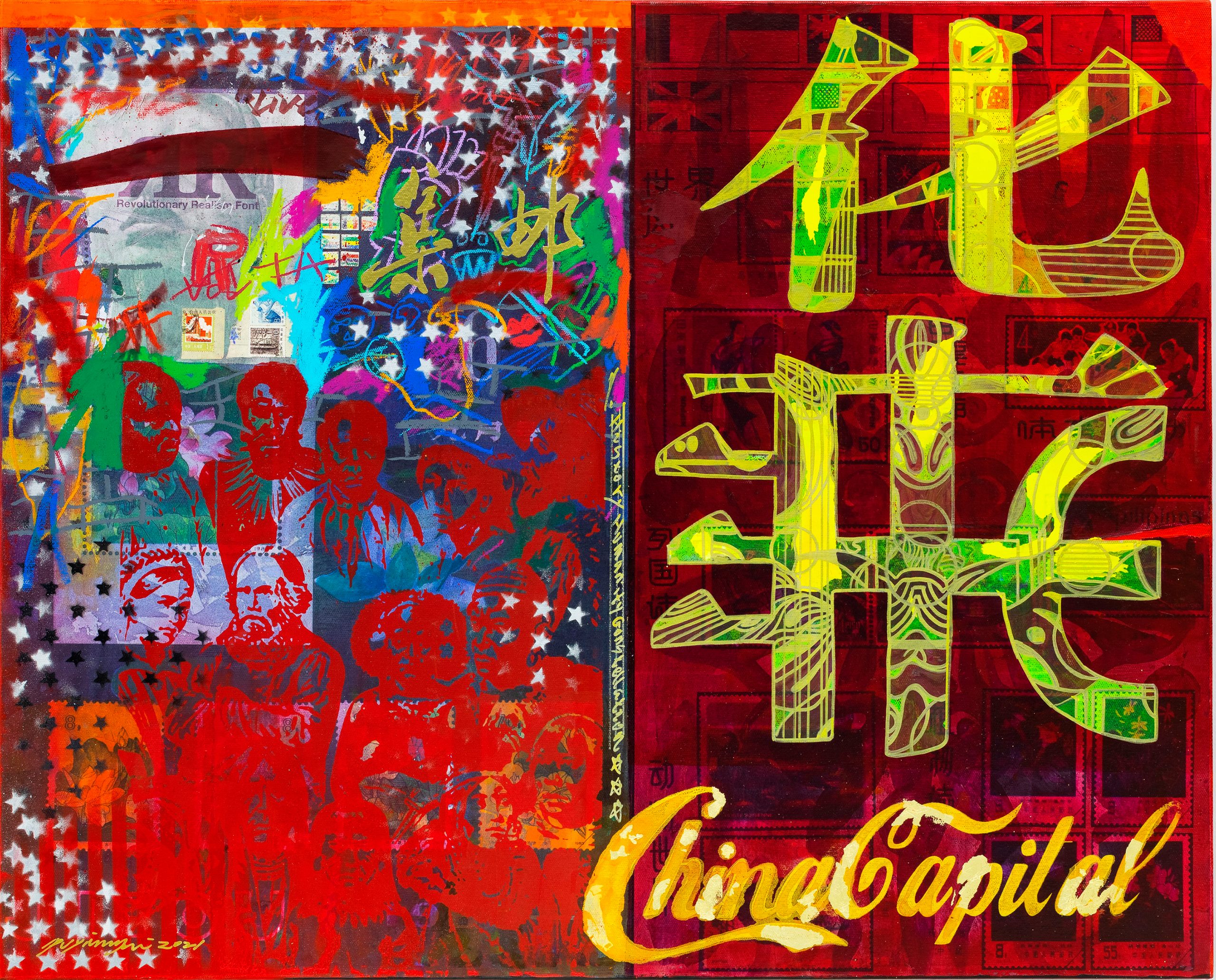

Pu Yingwei. Stamp Collecting: Hua (Intellectual History). 2021.Oil and acrylic on canvas, paper collage, stamp, screen-printing, solid marker, oil pastels, gold leaf, transparent watercolour, paint pens. 100×80cm.

Pu Yingwei was born in 1989. He lives and works in Beijing, China. In 2013, Pu graduated and received his Bachelor’s degree from Sichuan Fine Arts Institute; in 2018, he graduated from the National School of Fine Arts in Lyon and received a Master’s degree with the highest distinction. Pu Yingwei’s work has been rendered as a conceptual art practice with an immense, Utopian passion. The artist interprets the multi-media and identity narratives he practices in the public realm as a total mobilisation. Using personal history as an absolute point of departure through various forms of work, including exhibition, writing, design, lecturing, and teaching, the artist attempts to produce metapolitics that transcends the great propositions of race, nation, and ethics. This metapolitics is as complex and paradoxical as the reality we experience.

In his recent practice, Pu Yingwei has discarded the subject of identity fluidity he has been working on since his time in France. He has instead embraced the division of ideological camps and the return of imperialism as the new context for his work. He researches extensively on and continues the visual legacy of Socialist Realism and 20th-century Avant-Garde art. Drawing from two heterogeneous and homogeneous visual cultures, revolutionary art and ideological propaganda, Pu forms his unique linguistic system and historical perspective.

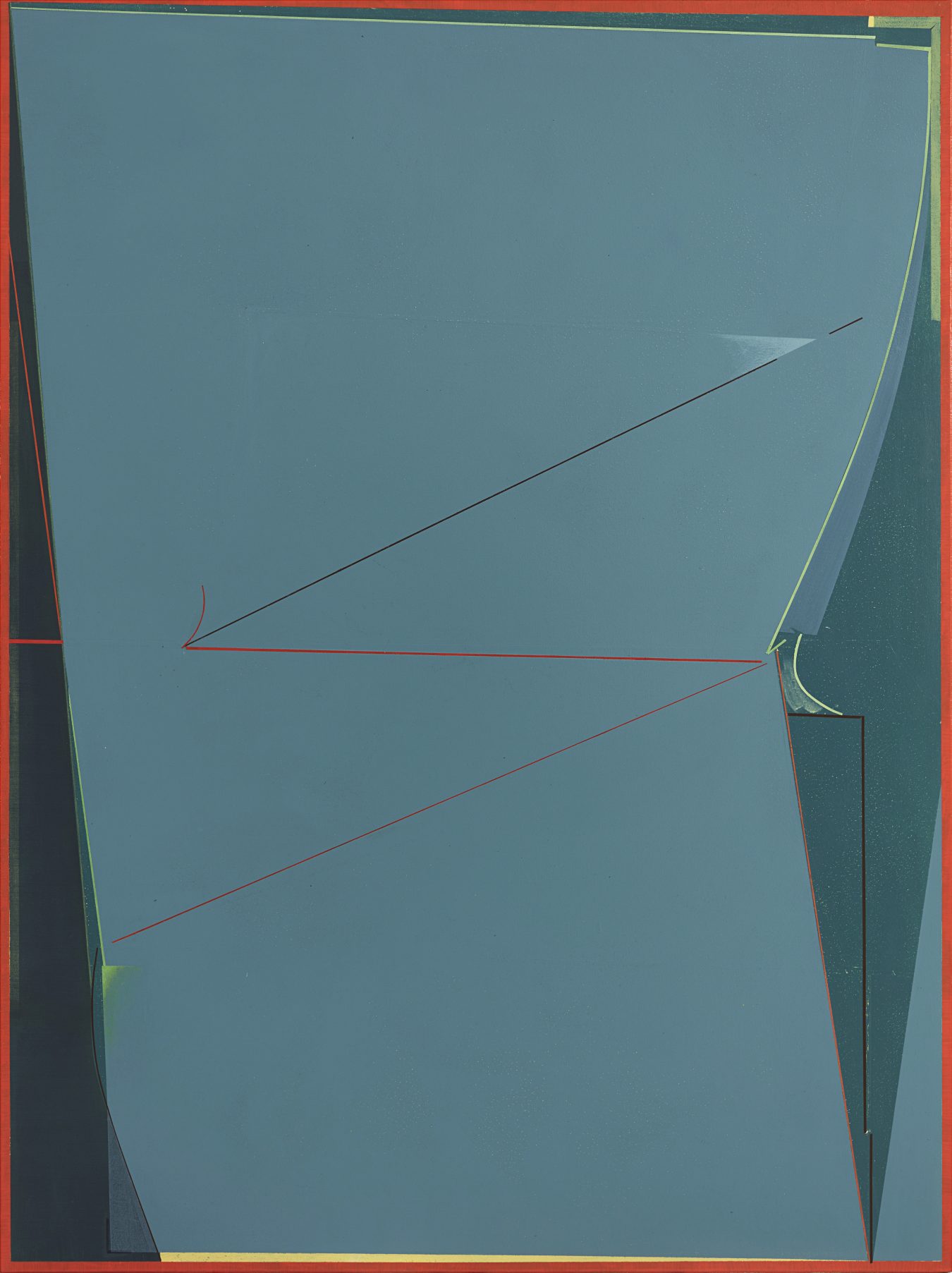

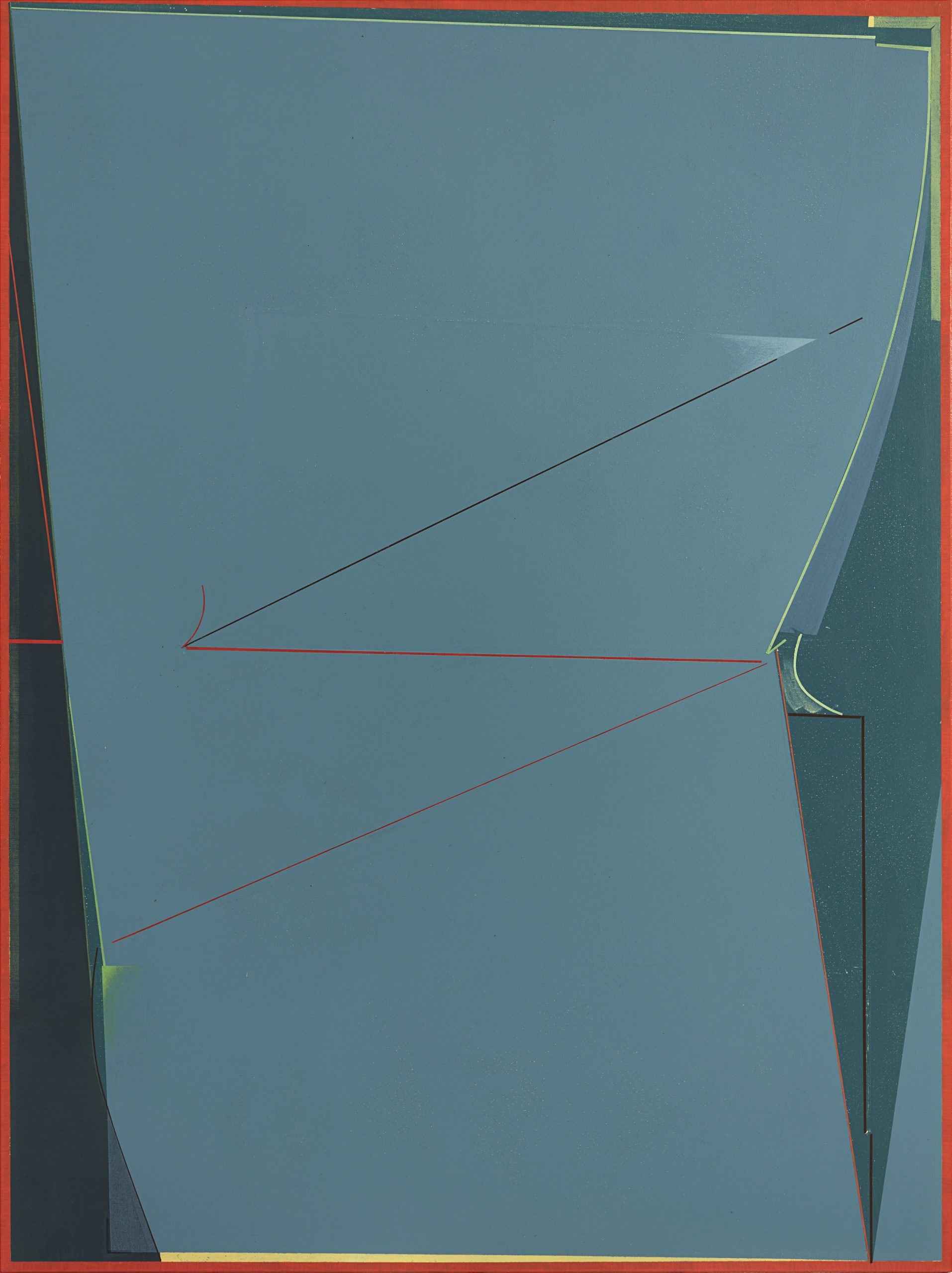

Qian Jiahua. Jet-Propelled. 2020. Acrylic on canvas. 160×120cm.

Born in Shanghai in 1987, Qian Jiahua graduated from the China Academy of Art in 2011. Qian Jiahua’s work is derived from her attention to the aesthetics of Bauhaus design and architecture, while the essence is saturated with notably private, situational experiences. The artist often translates her interests and sentiments about her surroundings into a flattened visual language with sharp manipulation. This manipulation of her work is also associated with her deliberate distance from the surrounding to maintain her sensitivity to different elements. Qian Jiahua often implies these feelings to the viewer in her naming of the paintings. Her earlier works hint at a sense of framed drama; later on, the natural, utopian, romantic narrative is presented in a breath between the lines and shades. The artist’s more recent works highlight her attention to the urban life experience. The confining structural and living spaces of contemporary cities have replaced the natural palettes of the past with architectural façades and textures. Qian Jiahua’s work fulfils an abstraction system with Eastern domestic attributes. And it is for this reason, her work is not based on Western abstraction, but rather, along with other modernistic painters, constructs the internalised emphasis on private feelings that artists are more concerned with, confronting the shifting social structures.

Wang He. Tardis: River and Mountain in Snow. 2021. Ink and colour on silk. 103×56cm, 56×56cm.

Wang He was born in 1983. After graduating from the Academy of Fine Arts of Tsinghua University in 2008, he joined the Palace Museum for replication of paintings and calligraphy. For more than ten years, Wang He has been refining his craftsmanship, which, simultaneously, has awakened his enthusiasm for creating underlying in the accumulation of aesthetics and self-cultivation. At a glance, he has implanted various visual elements outside of Chinese tradition and more contemporary cinematic language into a foundation paved with classical Chinese calligraphy and painting.

View Outside of Window is a series of diptych paintings Wang He had begun creating in 2018. View Outside of Window series often parallel dual perspectives, manifesting a distant view referenced directly from the classical painting on one side. In contrast, the other side penetrates deeply with a decidedly distinct viewpoint from the original. Through the window of a residence in the painting, we look out to another slice in the world of classical painting. In Tardis: River and Mountain in Snow, the classical imagery references a painting by Anonymous from the Southern Song Dynasty, now part of Taipei’s National Palace Museum’s collection. In the original work, the upper right corner of the painting contains a text inscription. Wang He appropriated the time machine from the famous British drama Doctor Who as a medium for passing through space-time, substituting the original inscription, and interpreting the perspective of looking out from the pavilion’s interior on the right screen. It is necessary to note that the perception of time-travel presented in Wang He’s work does not propose a strict perspective but fundamentally a consequence of the artist’s conscious decision. Wang intends to provoke the audience’s experience of the charm of traditional painting and calligraphy through the viewpoint of time travel.

Wang He. View from the Mirror: Returning from Spring Trip. 2021. Ink and colour on silk. 36×36cm×2.

Comparatively speaking, View Outside of Window-Returning Late after Spring Outing is an attempt at the medium of a new perspective. It is also an augmentation of the View Outside of Window series. Wang references from the Album of Returning Late after Spring Outing by Anonymous in Southern Song Dynasty. Observing the horserider figure in the original painting of Returning Late after Spring Outing, Wang He noticed that the posture of that figure looking back seems to reveal the existence of another outside the painting. To complement this narrative, on the left screen of the diptych, a Newtonian telescope, a scientific object, is employed to elevate the expression of this tension. Additionally, Wang He is cautious in setting the scene. The traditional elements referenced from a classical Chinese study in the painting, including the Songhua inkstone, paperweight, table screen, and the water basin, are all thoughtfully considered. What’s worth noticing is that in traditional Chinese paintings, the screen on the right should have a rounded rectangular composition. Due to the intervention of the telescope, the artist adjusted it to a perfect circle. Simultaneously, the painting of the traditional round-edged rectangle is recreated in miniature on the left screen. Supplementing a contemporary perspective to traditional paintings, in the limited alteration under the artist’s adjustment, the viewer’s perception of the two screens has undergone drastic changes, which is precisely the profoundness of this work.

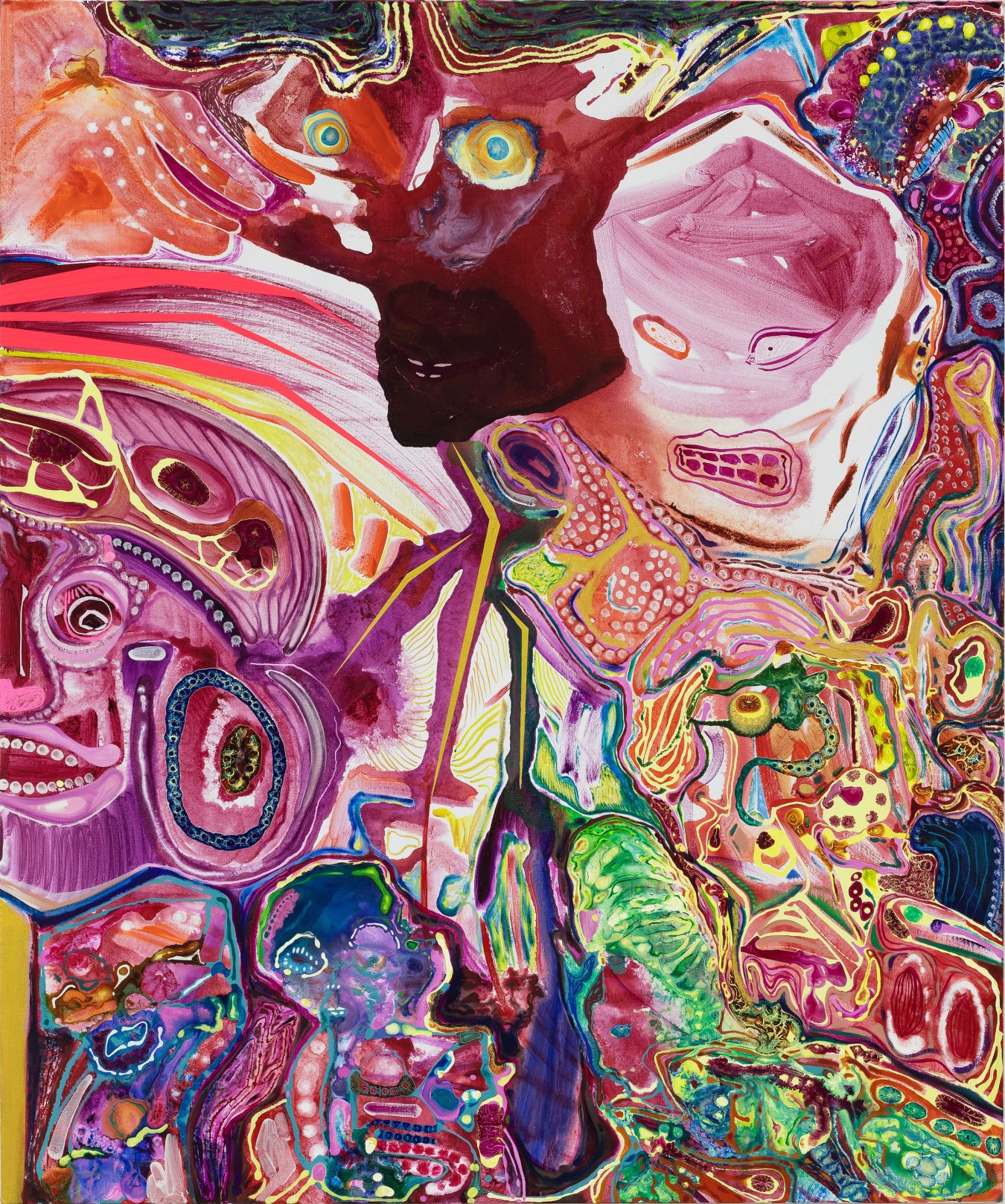

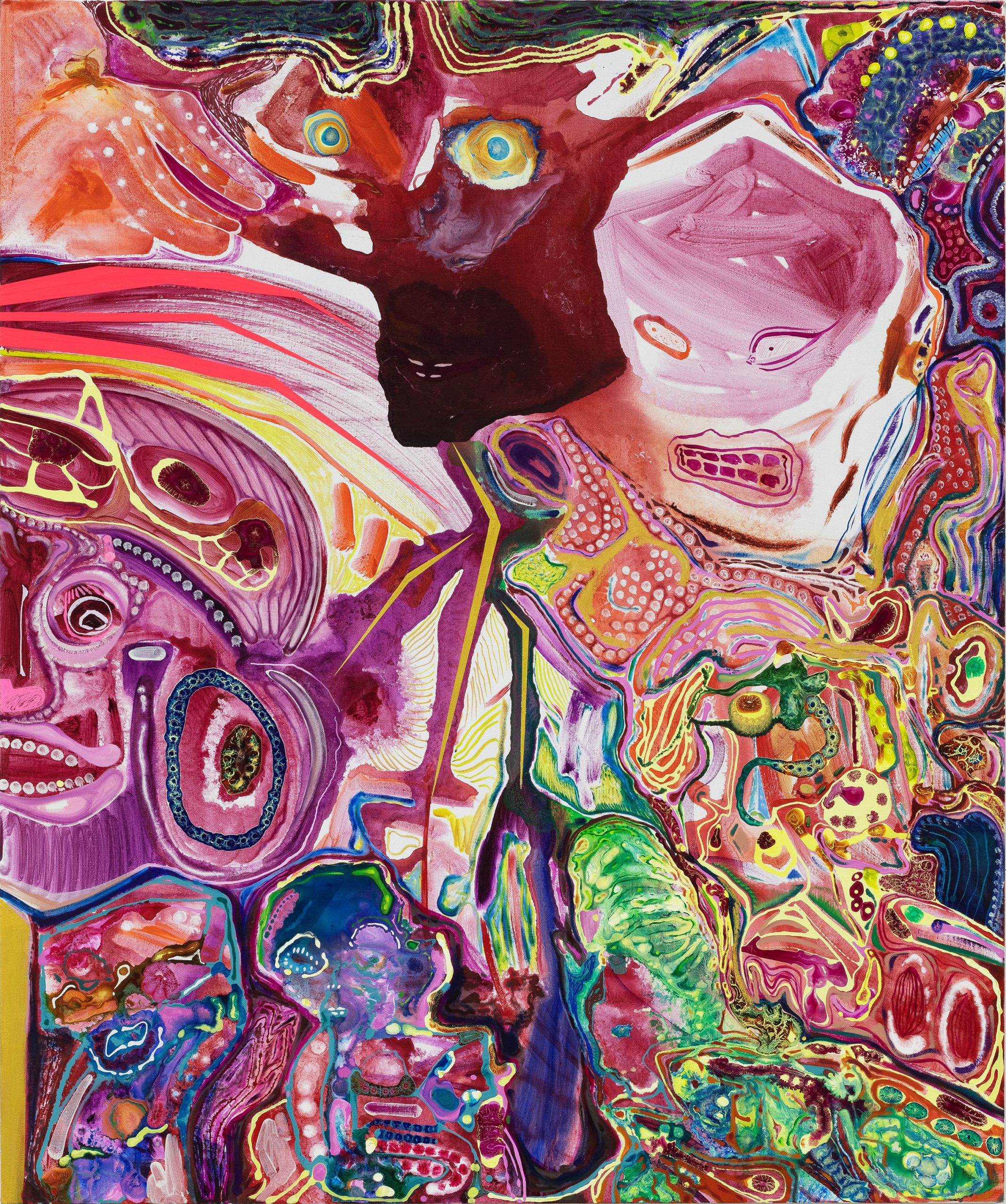

Zhang Ji. While we took a selfie, a blooming started. 2021. Oil and acrylic on canvas. 180×150cm.

Born in Beijing in 1993, Zhang Ji graduated from Maryland Institute College of Art and School of the Art Institute of Chicago with a BFA and an MFA degree, respectively. In Zhang Ji’s work, there are often shifting compositions, bizarre shapes of light areas and lines, which usually partition and compress the human body (deformed body parts, exposed organs, peculiar exposure, worship of genitalia, and totem-like torsos). The artist prefers curved lines, diagonal or vertical, over horizontal framing. The division by brushstrokes, traces, and lines presents Zhang Ji’s version of bodies or his whole world of painting as restless and unstable. Additionally, Zhang Ji has his metaphysical understanding of the body, and most viewers find it hard to expound on his highly personal style. We can only summarize that the body is a public medium of sociality, and the package of modern civilization has shadowed the social properties of its structure. Thanks to the magic of painting, we can unravel everything and make public every unspeakable secret about the body.